Preparing for Patient Deaths and Postmortem Care

By: Emily McKisson, MS, BSN, RN, CNOR

Published: 10/9/2024

One of the most traumatic experiences a novice nurse can face in the OR is a patient’s death. The first time I experienced a patient death, it was memorable in a way that I never expected. It was a very surreal moment when I realized the delicate balance between life and death; the fast, unease sound of the EKG monitor slowing, then stopping. As nurses, our foundation for providing care does not end when our patient’s life does; in fact, some may argue that this is when the true work of human compassion begins.

As a nurse educator, I wanted to prepare novice nurses for this exact scenario. Further, I wanted education around the topic to be real; to include the down-and-dirty processes that we must follow and the caring practices that will prepare our nurses and surgical technologists to provide the most compassionate care possible.

My audience was the nurses and surgical technologists in our cardiac and vascular ORs. These surgical services encounter the highest acuity patients and unfortunately find themselves in circumstances where patient outcomes can be poor, regardless of intervention. I wanted to prepare staff for the worst-case scenario: on call, three in the morning, amidst peak REM, awakened with instruction to report into the hospital as soon as possible. A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is en route to the surgical unit and immediate intervention is required.

Planning

To assist with the planning and execution of this group education activity, I solicited the expertise from one of the unit’s veteran nurses. Her tenure on the unit as the night shift charge nurse put her in a unique position of having the most experience with patient death and postmortem care. This partnership proved fruitful in more ways than one; it demonstrated the ability to appreciate the strengths our clinical staff members have—each in their own unique way, to showcase her expertise as a true patient care advocate and to provide a memorable group education session.

At the beginning of the activity, we had all staff members listen to our Decedent Affairs representative speak about the notification of death process and institutional communication protocols. After this presentation, we divided into two groups. We purposefully had a random mix of nurses and surgical technologists in both groups to encourage teamwork and collaboration. Each group would split the hour-long in-service time into two 30-minute mini-sessions: the first was in the OR for the postmortem process and the second was a field trip to the morgue. Once their first group session was over, they would switch to the next.

The Postmortem Process

In the OR, staff members were surprised, confused, and humored by who they saw lying on the operating table: one of our vascular surgeons (Figure 1). As our expired patient, he helped create a fun learning environment where this morbid topic could temporarily transform into humor. We wanted to teach a few things in this group, including postmortem cleaning of the patient, preparing the gurney to receive the body, how to identify the patient, and most importantly how to prepare the patient to be reunited with their loved ones.

Figure 1. A vascular surgeon plays the role of the patient.

To demonstrate the postmortem cleaning of the patient, we instructed our teams to use warm saline to wash the patient. Our surgeon patient was equipped with a Foley catheter, a central line, and an endotracheal tube. We reviewed our institutional protocol to understand which of these items could be removed and which items had to stay and the rationale for why. It was important for our surgical teams to understand that a death in the OR typically results in a coroner’s case; meaning unexpected deaths may require autopsy. For these referrals, it was important to keep all of the invasive lines. If the surgeon communicated that the coroner deferred the case and therefore an autopsy was not warranted, we were able to remove invasive lines.

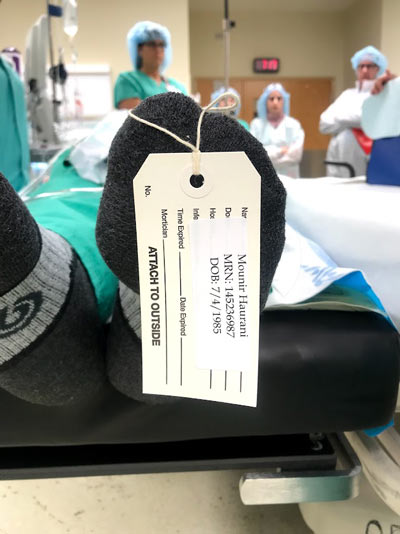

We demonstrated how to place the body bag on the gurney under white blankets, mostly to obstruct this from the view of the loved ones. For comedic relief, we prepopulated patient labels to appropriately affix to the patient’s toe (Figure 2), the relevant paperwork, and the body bag. Lastly, our veteran nurse shared a trick to prepare the patient to be reunited with their loved ones. She explained that, in her experience, loved ones typically touch the patient’s head, chest, and hands. Once the patient is moved from the operating table to the gurney, these are the areas where she places warm blankets (Figure 3) so when the final reunion does occur, the patient appears warm to the touch.

Figure 2. Patient label affixed to the toe.

Figure 3. Warm blankets placed on the "patient."

The Morgue

In this group, we walked the path that we would be taking a morgue cart to the morgue for the worst-case scenario previously mentioned. With the assistance of our Decedent Affairs representative, we also provided education on how to check in the patient, how to complete necessary paperwork, and where to store the patient in the cooler. For many of our staff members, this was the first and only time they had visited a morgue. Visiting as a group and having the support of their peers made this part of the educational session less scary and intimidating. Important to note: our patient did not actually ride in the morgue cart to the morgue.

Lessons Learned

Postmortem care can be emotionally taxing and, to be honest, scary. With the help of our veteran nurse and a willing surgeon volunteer, this education topic was transformed into a humorous, engaging, and hands-on activity. I recommend scheduling this annually and throwing in a few twists to keep people guessing. Sidebar 1 provides a list of common questions and answers about patient death and postmortem care. Sidebar 2 provides some tips on coping with death that can be shared with learners.

Sidebar 1. Common Questions and Answers About Patient Death and Postmortem Care

- Who is responsible for alerting the patient’s family member or next of kin that a death has occurred?

- Check your institutional policy on postmortem notification; however, this is ultimately the attending surgeon’s responsibility.

- What should I do if I am called into a trauma or emergency and my patient expires?

- Check your institutional policy for directions; however, know that you are not alone! Most hospitals have nursing supervisors or hospital administrators who are available 24/7 for consultation and direction. One of the important steps that nurses should be prepared for is notifying the organ donation organization in their state, which typically must occur within 60 minutes of the patient expiring. This is an important step if the patient is a registered organ donor.

- How would I know if the patient is an organ donor?

- You likely would not know this information if this was an unexpected death. Notifying your local or state organ donation organization will assist with locating this information.

Sidebar 2. Tips on Ways to Cope with Death to Share with Learners

- Seek the support of your surgical team; a debrief of the event can be a great way to understand the event and to know how to improve processes over time.

- Connect with your leadership team; unexpected deaths can be traumatic to a novice and veteran nurse alike. Seek the guidance from your leadership team to connect you to institutional resources that can offer additional support, such as the chaplain or employee assistance programs.

- Give yourself some grace; it can be emotionally difficult to cope with a patient death and if you find yourself struggling, know that this can be a normal human response. Underneath your RN badge is a whole person, and your feelings and coping mechanisms are an important part who you are as a person and as a nurse.