Intraoperative Patient Positioning: Decreasing the Risk of Brachial Plexus Nerve Damage

By: Brianna M. Sullivan, EMT; Kelsey Lane, BSN, RN; and Megan Pelley, BSN, RN, CPN

Published: 11/2/2023

Nerves transmit information between the brain and the body. Some of them send signals that cause the body to move. Others transmit details regarding discomfort, pressure, and temperature. If a nerve is compressed, cut, or improperly stretched during surgery, it can be susceptible to permanent damage. The symptoms of nerve injury can range from palsy to tingling and discomfort.

Health care professionals should focus on one essential factor when considering how to reduce the likelihood of intraoperative nerve damage: patient positioning. Nerve injury can occur if a patient is positioned improperly during surgery or remains in the same position for an extended period. In addition, when the patient is awake, pain and pressure receptors warn against unnatural stretching and twisting of tendons, ligaments, and muscles.1 However, the anesthetized patient cannot respond to an exaggerated range of motion and thus must rely on the surgical team for proper positioning. Proper patient positioning and the use of positioning devices can help lower the risk of intraoperative brachial nerve injury.

Anatomy

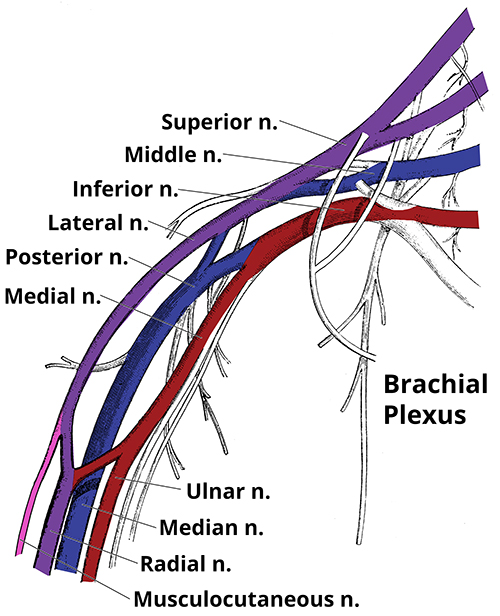

The anatomical position of the brachial plexus is critical to understand to determine its vulnerability during surgery (Figure 1). Because of its proximity to bony structures, the brachial plexus is especially prone to injury. The thoracic and cervical portions of the human spinal cord form roots that intertwine and make up nerve bundles. The brachial plexus is between the first rib and the clavicle, and its width extends from the anterior scalene of the neck to the pectoralis minor, where cords form within the axilla to give rise to the upper extremity nerves.2

Figure 1. Anatomy of the brachial plexus.

The Role of the Nurse

Before the patient’s arrival to the OR, the surgical team should have already developed a plan for positioning the patient. Think about where anatomically the procedure is taking place. How will positioning help with access to the surgical site? Think about laterality. Is there a positioning device that will be needed? What about the patient’s size/weight? Will they need a bed extension or additional padding or supports? The same with the patient’s history. Do they have any unique anatomy, range-of-motion limitations, or any history that impacts circulation or sensation? Positioning is to be tailored to the specific needs of each individual patient and needs of the surgeon. As always in the OR, it takes a team approach and the whole surgical team to work together to create the optimal position for the surgery and for the safety of the patient.

The brachial plexus can be particularly vulnerable in the supine position. Typically, when patients are positioned supine, or flat on their backs, arms are extended bilaterally on arm boards. The brachial nerves are vulnerable if the arms are extended past 90 degrees or if there is rotation of the arms so palms are facing down. To avoid injury, the arms should not be hyperextended more than 90 degrees and the palms should be facing up on arm boards, with padding to secure position (Table 1). In addition, the head should be aligned with the neck.

Table 1. The Dos and Don'ts of Supine Positioning

Do | Don't |

|---|---|

Extremities secured and supported on arm board at angle ≤ 90 degrees | Extremities not secured and hanging off arm board at angle > 90 degrees |

Palms facing up | Palms facing down |

Fingers extended | Fingers closed |

Head facing up | Head rotated to side |

The brachial plexus also is vulnerable in the sitting and Trendelenburg positions. For the sitting position, surgeons may adjust the OR bed to resemble a beach chair or use a beach chair positioning device that attaches to the OR bed. This position is used for many surgeries, including nasopharyngeal, facial, neck, and breast procedures.3 In addition to proper padding and arm placement, a roll may be placed under the neck to provide better access to the surgical site and prevent hyperextension. In the Trendelenburg position, shoulder braces can cause brachial plexus compression.3 Instead of using shoulder braces, AORN recommends using viscoelastic gel or convoluted foam overlays, or vacuum-packed positioning devices to prevent the patient from sliding.4

The duration of surgical procedures also must be considered. During lengthy procedures, a respite period or recommended 15-minute interval in which the patient is placed in a neutral position can be necessary to avoid nerve damage.1 The perioperative nurse may be responsible for initiating a time out to ensure both patient and team safety during this transition. It is essential for the nurse to document any changes in positioning, in addition to noting any added padding or straps or excess positioning devices. It also is important to check on the patient’s positioning during surgery to ensure that the extremities remain fully supported. It should be noted that accidental hyperextension can be hidden by surgical drapes. If any adjustments are made by the team at the field, such as sitting the patient up and then back down, nurses should speak up if there appears to have been any shifting or they need to check under the drapes to ensure that alignment has been maintained.

Pediatric Considerations

Because of their smaller physique, children may not require arm boards. Depending on the patient’s size and stature, there may be adequate space for arms to lay comfortably alongside the body. They may also be positioned with their arms crossed over their chest, with sufficient padding and secured with safety straps. When tucking the arms close to the body, palms should face the body, and the draw sheet should be tucked under the patient and not the mattress to avoid impaired circulation or nerve torsion, which can lead to compartment syndrome.

Maintaining neutral patient positioning will result in safer intraoperative patient care. For example, one retrospective study of patient positioning during the pediatric Nuss procedure compared the raising and extending of patients’ arms over their heads at 90-degree angles with arm placement in an arthroscopic sling device that suspends arms in a neutral position.5 (The pediatric Nuss procedure is a surgical treatment of pectus excavatum, which is a congenital condition in which the patient’s breastbone is sunken into their chest; positioning includes intraoperative manipulation of the patient's arms to achieve the surgical goal.) Several patients who had their arms extended above their head at 90 degrees reported injuries, but no brachial plexus injuries were reported for patients placed in the arthroscopic sling in neutral position.5

Conclusion

Optimizing strategies to maintain proper anatomical alignment and utilizing best practice for padding and positioning will reduce the risk of brachial nerve injury. Since a patient cannot move, feel pain or discomfort, or reposition themself during surgery due to the anesthesia, the perioperative nurse has a duty to act as the patient's advocate. Nurses should feel empowered to be the voice of the patient and put time and care into positioning.

References:

- Hewson DW, Bedforth NM, Hardman JG. Peripheral nerve injury arising in anesthesia practice. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:51-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14140

- Leinberry CF, Wehbé MA. Brachial plexus anatomy. Hand Clinics. 2004;20(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-0712(03)00088-x

- Duffy BJ, Tubog TD. The prevention and recognition of ulnar nerve and brachial plexus injuries. J Anesth Nurs. 2017;32(6):636-649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2016.06.005

- Guideline for positioning the patient. In: Guidelines for Perioperative Practice. Denver, CO: AORN, Inc; 2023: 701-750.

- Fox ME, Bensard DD, Roaten B, Hendrickson RJ. Positioning for the Nuss procedure: avoiding brachial plexus injury. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(12):1067-1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01630.x