- Home

- Article

Lessons Learned From the RaDonda Vaught Ruling

By: Jared Bilski | Editor-in-Chief

Published: 2/8/2023

Nearly a year after the landmark case, providers discuss a profession in peril, shared accountability and the future of ‘Just Culture.’

When RaDonda Vaught was found guilty of criminally negligent homicide for a fatal medication error that she self-reported, the ruling sent shockwaves across the medical community and left nurses fearful the criminalization of medical mistakes could jeopardize both their professional livelihoods and the transparency and culture of safety needed to keep patients free from harm.

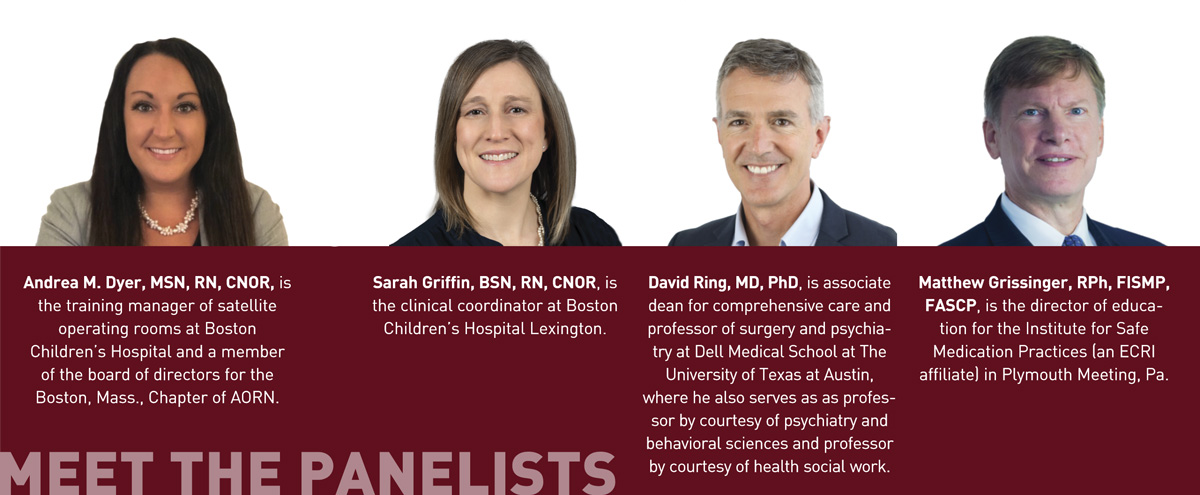

During Ms. Vaught’s sentencing, Outpatient Surgery Magazine offered comprehensive coverage of the case and its immediate impact. Now, almost a year later, we’re looking at the larger, long-term implications of this landmark court case and its impact on patient safety and the nursing community at large. To do this, we convened a panel of providers and industry experts for a passionate roundtable discussion on the subject.

The Discussion

(Note: Panelists’ responses were lightly edited for clarity and space.)

OSM: What’s the first thing you think about when you think about RaDonda Vaught and the landmark court case that followed?

Andrea Dyer:

For me, it was a major injustice. What does this ruling do for the “Just Culture”? (See “Key Terms,” below.) What does this do for the nursing world? At the time, I had seven Periop 101 nurse residents, and they were literally

in a panic. It was like the shot heard around the nursing world, and it was terrifying because it felt like everything I’ve spent the last 20 years working on — Just Culture in nursing and being upfront about medical errors — was

just undone. I feel like we were taking steps backward and removing the progress that we had been working on for the past 20 years.

David Ring: I agree with thinking immediately about David Marx’s Just Culture framework. Working in quality and safety at Mass General (MGH) for 16 years, within the Just Culture framework, safety starts with: 1.) human system fix and 2.) drift from best practices and coaching. If this [Vaught’s case] is an example of a third category of recklessness, which merits punishment, it would be much more constructive to operate and discuss it within the Just Culture algorithm and be very clear which elements of it represented recklessness and merited punishment. In the absence of clear and obvious recklessness, then this is very disruptive to the safety culture. In my work, recklessness is just so rare. Other than some physicians who are impaired by substance misuse, we never saw recklessness.

Matthew Grissinger: I’ve been working at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) for 22 years, and I feel like nothing’s changed. To Err Is Human came out in 2000, and we’re still having the same discussion today — 23 years later. It’s very frustrating that we seem to make no progress. The Just Culture model is all about understanding why errors occur, that humans make errors, and organizations are inadvertently setting practitioners up for failure. To some degree, in this case in particular, organizations allow for at-risk behaviors. My overall frustration is that from a leadership perspective, we’ve made no forward progress.

OSM: What do you feel the implications — both on a long-term and a short-term basis — will be for nurses and for healthcare systems at large following the RaDonda Vaught case?

AD: Being in administration,

we were like, This just can’t be. We can’t just put blame on nurses. A lot of the stuff they [Vanderbilt] did were red flags to me in this role. One of the things that I did the moment I saw everyone panicking was reach out to my

sister, who’s a lawyer. She put me in touch with a criminal defense attorney in Boston. And I said, Can you help me understand more about this case? Right now, I’m really upset with the DA. I’m upset with the police. I’m upset with the hospital, and I don’t know all the details of what’s going on.

What I do know is that in my administration role, I would take responsibility. When nurses come to us with errors, we are responsible too. We’re the ones who are ensuring patient safety, putting policies in place, making sure we’re educating the educators and giving staff the education they need to not make these missteps. If we don’t do this, how can we avoid this type of injustice in the future? I will use that word over and over again, because that’s what this case was: unjust. After the verdict, I looked up the AORN statement on medication errors and felt really proud to be a part of an organization that would put that out and support it — just like we do at Boston Children’s.

In the long term, I think that this case is going to make the nursing community really think about malpractice more — and nurses will become more educated on it.

Sarah Griffin, BSN, RN, CNOR

Sarah Griffin: Short term, I think the concerns were that nurses are now going to cover up their errors in fear of reprisal. In the long term, I think that this case is going to make the nursing community really think about malpractice more — and nurses will become more educated on it.

DR: I think this case could actually bolster a safety culture. Even if this were one of those exceptional cases of recklessness, there’s probably a better way to handle it than taking it through the system of the courts. If you think about the examples of recklessness that we would all agree on — nurses intentionally killing patients and other real outlier situations where mental illness is involved — it’s not just, “you’re a bad apple, you should be thrown in jail.” It’s always much more complex than that. In fact, in the last 20 years of quality and safety work at MGH, other than substance misuse — people taking things out of the medication dispensing cabinets or showing up impaired — recklessness has not been an issue we’ve seen. We’ve certainly seen drift. And we’ve had to work to get people back to doing things like effective timeouts, signing the operative site in the operating room and double checks on medications and blood transfusions and identifying medications that are easy to mix up. We’ve had to work at that — there’s a lot of coaching going on. But recklessness is exceptionally rare. And yes, it should be punished. But there should be ways of having that accountability for recklessness outside of the legal process — unless it’s absolutely egregious.

If I were still working in quality and safety operations, I would absolutely use this case as a point of discussion and say: No one in our organization will be subjected to this treatment. Everyone is going to be operating with the Just Culture algorithm.

MG: Short-term, the fact that nurses and any healthcare practitioners are going to be afraid to say anything or mention or discuss errors that happen — whether they’re a result of a human error or at-risk behavior — is a major concern. But regardless of short-term or long-term, I’m still concerned about the legal system’s involvement. There are a lot of things the prosecution said that could easily have been contradicted or said to support the defense. My biggest fear here is that readers don’t fully understand the Just Culture model. During my work in outpatient surgery departments, I’ve found that many facilities don’t know what Just Culture means. That is a major concern, because we’re throwing around words like “recklessness” and there are people who will read this article and notknow what that means. And it all goes back to the fact that we’ve gotten nowhere in health care with this model.

The long-term implication is maintaining status quo. Because I cannot tell you how many times I’ve given presentations and interviews about this case, and people don’t know how to respond to practitioners involved in errors.

DR (responding to Matthew Grissinger’s answer): Maybe “recklessness” isn’t even the right word. Maybe we need to work on that. But at least it’s an opportunity to have that discussion. A chance for each organization to say, What does accountability look like? What merits some form of remediation or accountability or punishment? And what would that look like? And what would be going on? If that was going to happen — Is it sociopathy? Is it some other kind of mental illness? I think it’s worth having that sort of discussion because the majority of what we’re doing in quality and safety is identifying human errors and creating system fixes, developing safety systems and making sure we coach people so that they’re always championing those systems.

Throughout our discussion, providers used many terms related to the “Just Culture” system created by David Marx. For reference, here are the definitions of several of the key terms that were repeated throughout the conversation in the context of the Just Culture framework, courtesy of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). For more information on this case and the Just Culture framework, ISMP offers a variety of resources at osmag.net/ismpresources.

• Just Culture. A system of shared accountability in which organizations are accountable for the systems they have designed and for responding to the behaviors of their employees in a fair and just manner. Employees are accountable for the quality of their choices and for reporting errors and system vulnerabilities.

• Human error. This is an inevitable, unpredictable and unintentional failure in the way we perceive, think or behave. It is not a behavioral choice — we do NOT choose to make errors, but we are all fallible.

• At-risk behavior. These behaviors are different from human errors. They are behavioral choices made when individuals have lost the perception of risk associated with the choice or mistakenly believe the risk to be insignificant or justified.

• Reckless behavior (or “recklessness” as used in this discussion). The conscious disregard of a substantial and unjustifiable risk. In comparison to at-risk behaviors, individuals who behave recklessly always know the risk they are taking and understand that it is substantial. They behave intentionally and are unable to justify the behavior (i.e., do not mistakenly believe the risk is justified). They know others are not engaging in the behavior (i.e., it is not the norm). The behavior represents a conscious choice to disregard what they know to be a substantial and unjustifiable risk. Key to this concept is that the individual must recognize the substantial and unjustifiable risk in order to disregard it. Therefore, they must reasonably foresee that their actions or inaction will or could create a substantial and unjustifiable risk.

AD: I think what everyone is saying is it goes back to education. I feel like with the errors, if we use words like “punishment,” it’s going to make people scared again and go back to not speaking up. I’ve had people years later come to me when I worked on the West Coast and tell me about errors they had made that they were too terrified to tell me about. Why did they even tell me in the first place? The guilt. There’s nothing worse than a guilty conscience. One of the first things I teach in my students is, I need to be able to sleep at night, so I have always, every day of my career, admitted when I’ve done something wrong. It’s one of the fastest and best ways to grow respect with doctors. They see that and then you’re gaining trust right away, and you’re not going to get in trouble. Something I teach from day one is that we don’t have a punitive culture; we have a learning, teaching, educating trust.

MG: I just want to add that Just Culture is about shared accountability. And for some reason we live in a bizarro world where accountability is supposedly only about frontline staff, and not the management. Remember, RaDonda was, in a way, set up to fail. There were a lot of system failures in her case, and we’re losing sight of that. The conversation is always about the punishment that happened, and I understand that. But healthcare practitioners are set up to fail in organizations or to make at-risk behaviors or poor behavioral choices, because they’re put in a position to need to use in at-risk behavior to get their jobs done.

OSM: Without going into specifics, one of the claims that was made was that there were overrides and workarounds in place that were ingrained in the culture. How common is this? And does it hint at an industry-wide safety problem?

AD:

We don’t have that problem where we’re allowed to override meds, but there were times in previous roles as a cardiac nurse where patients would be going into congestive heart failure, and I’d be overriding Lasix, morphine —

anything. Before this case, I would have never thought twice about that. Now, looking back, I’m like, That’s terrifying. Meds look the same, and they sound the same. I’m pulling out Lasix, or maybe I’m pulling out something

else — and I could kill someone. It’s terrifying. Overriding meds should be a thing of the past. They put protocols in place to protect us, and we need to follow them.

SG: We were talking about shared culture. In that, where is the quality — the responsibility of quality to be sure that there aren’t any workarounds? Is that always going to be there? Is there a way to mitigate these issues, so there arent the workarounds? Nurses are forced to do the workarounds when it comes to emergency situations. So the question is: How are we working together to not have that be the case — to have enough staff on hand, to have enough resources to not force those workarounds?

DR: We’re having the discussion that we tend to want to have after any adverse event, or even good catch in our organizations. How do we learn and improve? I think what we’re hearing is we want to work in organizations that have a safety culture and a growth mindset, and understand that to err is human. We are expecting mistakes; we’re expecting errors. And we want to set up systems that catch those errors before they cause harm. We also want a culture that rewards, encourages and fosters open communication and speaking up — even when you’re just a little uneasy about something. It doesn’t have to be that something goes wrong, you just notice something that could be a latent error or something that could become an error or even harm later on.

People pay attention to that from the leadership all the way down. And that’s acted on for the patient’s benefit, but also for the clinicians, because we want to feel like we take on high-stakes, high-risk jobs and activities because there’s nothing more important to humans than their health. We want to know that we’re in complex environment where many, many things can go wrong and adverse events happen without anybody being flawed or wrong or deficient or a bad apple. We want to know that the system understands that and supports us.

MG: Unfortunately, we’re forgetting what led to this override in the first place. That’s really important to understand, and I’m concerned by the way the media has portrayed this as, Oh, she overrode the safety protocols. Well, the story of it was, this patient didn’t have an order for vecuronium. Nurses are put in the position to have the ability to withdraw medications without orders. That is a decision made by organizations and a technology is being used. Now in this case, as stated earlier, there were issues with the communication between the ADCs and the order entry systems that led to them needing to put everything on override in the first place. Just keep in mind, the issue is not the override. It’s the fact that what led to the override was, a doctor ordered Versed, she went to a machine to type in VE only, and Versed was in the system as Midazolam. And the only drug that came up was vecuronium. So she could pick it and go with it. In a strong system with an ADC machine, she should never be able to pull that drug in the first place. Override is not the issue here. She was put in position to have to do the override to keep moving. She was set up to fail. And not just RaDonda. There are many times nurses are put in positions, especially by doctors, to be prepared to have drugs ready and pull drugs without orders. That’s the problem.

OSM: What steps can healthcare leaders take to ensure that staff feel supported when it comes to self-reporting, disclosing mistakes or near misses, while also maintaining the absolute safety of the patients involved?

AD: Be aware

of your discomfort levels, and what you’re comfortable with. Encouraging staff to come forward with questions is one of the biggest takeaways. The second that we start new staff here, we meet them, we make sure they’re comfortable with

us, and we’re building that rapport, so that they’re always comfortable to come into our office. Have an open-door policy so that any concerns staff have are addressed. And that goes back to just building that rapport with staff so if

they do have discomfort, they come to you. When I was in a nursing role working in the OR, I would do anything and work so hard for a leader who I felt like was supporting me, wanted me to be there and was positive.

I feel like we were taking steps backward and removing the progress that we have been working on for the past 20 years.

Andrea M. Dyer, MSN, RN, CNOR

SG: I think it’s also important that when nurses are coming to you, they’re able to come to you with questions — and without fear of judgment. Personally, when someone comes in and says, I’ve made a mistake, I thank them for coming forward. I encourage all staff to come forward, and I work really hard to make sure they feel supported — not judged — so they don’t have that fear of coming forward.

DR: If anyone wasn’t familiar with Just Culture, this Roundtable will update them. And if you want people to enter the medical field and stay in the medical field, the leadership of the organization must live and breathe quality and safety. There must be a safety culture in place and being nurtured every single day.

MG: Leaders need to understand the tenets of what people call a High Reliability Organization (HRO). And the first tenet, the first part of that or characteristic is what they call a “Preoccupation with Failure.” Going back to what was said earlier, I want nurses to be comfortable to come and speak up with special concerns. I want leaders to ask them about their concerns. Don’t wait for nurses to come to them. Leaders in HROs are aware that mistakes are going to happen. And it’s always going to happen today. It’s going to happen tomorrow. What is their preoccupation with failure? How are they proactively addressing these issues?

I hate to say I don’t want to hear about the errors, but I want to hear about what I’m doing proactively to address this concern before it happens. Thirty years later, we’re still reacting to problems after they occur. What are leaders doing to proactively identify breakdowns, workarounds, at-risk behaviors and system failures within their outpatient surgery departments proactively before patients are harmed? OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)