November 25, 2024

New York City’s Mount Sinai Health System has opened Peakpoint Midtown West Surgery Center, a 25,106-square-foot multispecialty ASC in Manhattan....

This website uses cookies. to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking “Accept & Close”, you consent to our use of cookies. Read our Privacy Policy to learn more.

By: Danielle Bouchat-Friedman

Published: 5/13/2021

Daniel Gomez, MD, FACOG, FACS, vividly remembers the day during his third year of residency when he was operating with one of his attending physicians. As they were sewing up the uterus during a C-section, the attending inadvertently stabbed him

in the index finger with a suture needle. “You always try to be as careful as possible, but you rely on the person who you’re operating with to use good technique and shield the needle,” says Dr. Gomez, who is now a board-certified

obstetrician/gynecologist at Holy Cross Medical Group in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Unfortunately, Dr. Gomez’s experience is the norm rather than the exception. In fact, he says the vast majority of surgical residents — upwards

of 90% — sustain needlestick injuries during their training.

He followed proper protocols after the injury occurred — removing his gloves, washing his hands and putting clean gloves on — and then reported the injury to employee health so he could get tested for HIV, syphilis and hepatitis. He also informed the patient of what had happened and received her consent to do a baseline blood test. Luckily, all tests came back negative, and Dr. Gomez wasn’t left with any permanent damage.

Dr. Gomez recalls being asked to complete online training that focused on needle safety. “I thought that was interesting, because I felt like [the facility] was telling me this injury could have been prevented.”

The refresher course was an institutional-level protocol, requiring anyone who sustained a needlestick injury to complete the training and show documentation that they were accomplished in proper handling techniques. Dr. Gomez thought the modules were informative, but they were too little too late to do much good in his case. “My biggest motivator for preventing a needlestick injury is having already suffered one,” he says.

The handling and disposal of sharps in the OR are high-risk tasks that endanger surgical team members on a daily basis, but many facilities still do not have viable action plans in place to prevent injuries from happening or responding properly when they do occur. While gains have been made, sharps injuries remain all too common. Unlike Dr. Gomez, your providers shouldn’t have to be motivated by past exposures to remain vigilant about protecting themselves from harm.

Amber H. Mitchell, DrPH, MPH, CPH, president and executive director of the International Safety Center (ISC), says current sharps safety practices are lacking. The ISC, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the safety of healthcare workers, issues annual reports about needlesticks and other sharps injuries based on data from the Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet) surveillance system. The 2019 report identifies nurses and physicians as the most-often injured healthcare workers, but also notes a high rate of injury sustained by residents, surgery attendants, technologists, phlebotomists and members of environmental services staffs (osmag.net/KmB4Pz). Of the injuries reported, 25% happened to staff members who were not the original user of the sharp item. The rate of injury is highest during the use of an item and before its disposal.

While the report states that over 50% of the injuries reported involved sharp medical devices with safety design features (recessed blades, retractable shields, blunted needles), over 70% of the time the safety mechanism was not activated. When a hand injury was sustained, the sharp item penetrated a single pair of gloves 61% of the time, compared with 35% of the time when the injured person was double-gloved.

It’s not just residents, surgeons and nurses who are at risk of occupational exposure to blood, bodily fluids and other potentially infectious materials. Amy Neubecker, RN, was working the overnight shift as the charge nurse at Michigan Medicine, a large healthcare complex associated with the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. One of the OR cleaners approached her with a hypodermic needle stuck in his finger. “He was cleaning a room and the needle was on the floor,” she recalls. “He bent down to pick up some trash, but didn’t notice the needle.”

Not only was he injured several hours after the last case of the day was completed, he had no idea what to do after getting stuck. “I walked him through the process in terms of who needed to be called and how to clean the injury, but it shocked me that only our surgeons, nurses and the techs knew what to do if they got stuck with a sharp,” says Ms. Neubecker.

The incident stayed with Ms. Neubecker, who made it a point to involve all departments in a newly created sharps safety committee. She found out a hospital-wide sharps policy had already existed, but it focused only on preventing needlestick injuries to surgeons and nurses in the OR.

“We realized we needed representation from multiple departments, so we included members of numerous disciplines, including nursing, environmental services and instrument reprocessing,” says Ms. Neubecker.

The committee collected sharps injury data from January 2019 to August 2019 that revealed 384 injuries in Michigan Medicine’s operating rooms involved sharps handling. Needlesticks were the leading cause of sharp-related harm.

"It shocked me that only our surgeons, nurses and techs knew what to do if they got stuck with a sharp."

— Amy Neubecker, RN

Based on these findings, the committee developed a set of standardized and institutionally supported best practices for reducing sharps-related injuries. All staff — not just surgeons and nurses — were informed of the standards in

order to improve consistency in sharps handling, and vendors were also contacted so the staff could review the latest safety-engineered devices.

The best practices the committee developed include:

• Double-gloving. Providers utilize an outer- and inner-glove indicator system. When the white outer glove is pierced, the color of the underglove shows through, letting the wearer know the double layer of protection has been compromised and they need to exchange their gloves for a fresh pair.

• Safer disposal. Staff at Michigan Medicine didn’t know the correct protocol for picking up sharps that had fallen on the floor during surgery. Some picked items up individually while others pushed the sharps into a pile with a disposable mop and then scooped up the debris with their hands — two options that increased their risk of getting stuck as evidenced by the environmental services worker whose injury prompted Ms. Neubecker to help revamp the sharps safety protocols. “We had no dustpans in the OR, so our cleaning staff picked debris up off the floor with their hands,” says Ms. Neubecker. “We addressed this issue by making sure dustpans and brooms are readily available on the unit.”

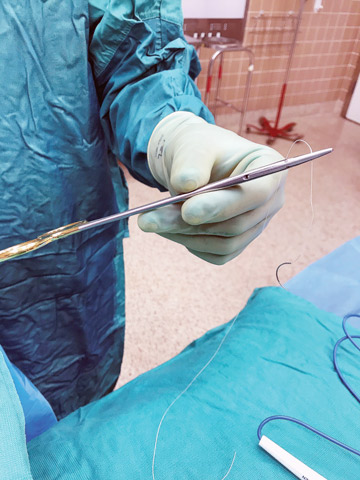

• Proper handling. Providers must use needle forceps to load and unload scalpel blades while always keeping the blade’s tip pointing away from them. When surgical techs pass scalpels to surgeons at the sterile field, they should hold the instrument with two fingertips positioned at the middle of the handle. This technique gives surgeons room on the handle to take hold of the instrument and allows the tech to quickly let go. Identifying hands-free neutral zones (a basin or pad) on the sterile field and using clear communication to identify when sharps are placed and removed from the zone also reduce the risk of injury.

Sutures should be secured in needle forceps for passing between providers, according to Ms. Neubecker. “Surgeons often pass sutures back to scrub techs with the needle hanging free, which increases the risk for a sharps injury,” she explains.

Sharps safety is an issue that needs to be front and center throughout the continuum of care. Providers must utilize effective prevention measures at all times, not just during surgery, says Dr. Mitchell. “They should think about sharps safety when removing devices from sterile packaging, during reprocessing and while disposing of them,” she says. “It’s important to think in terms of the hierarchy of controls and process flow, rather than only at the device and work-practice level.”

While the staff at Michigan Medicine is pleased with the best practices implemented to reduce sharps-related injuries, sharps safety is an issue that demands constant attention. “Continued work is needed to educate staff on safe handling through product evaluation, evidenced-based practices and campaign messaging,” says Ms. Neubecker. OSM

New York City’s Mount Sinai Health System has opened Peakpoint Midtown West Surgery Center, a 25,106-square-foot multispecialty ASC in Manhattan....

The new Irrisept Accessory Kit, now available for use with Irrisept Antimicrobial Wound Lavage, provides clinicians with more ways to use the trusted irrigation device....

As a leader, you need to look ahead for long-term solutions to an ever-changing environment while at the same time dealing with daily challenges....