- Home

- The Magazine

- Article

Power Shift

By: Outpatient Surgery Editors

Published: 5/1/2024

An inside look at the many factors driving change in the ASC ownership market.

As longtime ASC physician-owners look to retire or cash out, many lack a clear succession plan to keep their businesses moving forward. Due to changing market conditions, younger surgeons who want to establish freestanding ASCs often lack to the capital required to do so. Because margins can be tight even at busy ASCs due to the value focus of payors, a capital infusion can be a welcome development.

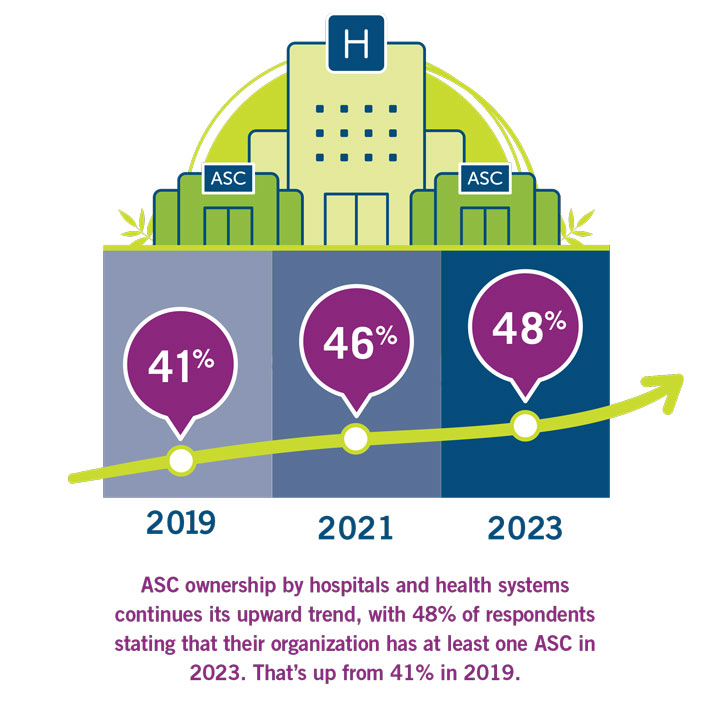

Existing and proposed ASCs are finding numerous well-heeled entities willing to give them that infusion. Private equity groups, ASC management companies and payors are more than happy to invest in ASCs or purchase them outright. Most visibly active in this area, however, are hospitals and health systems, which increasingly are looking to form ASC joint ventures with physicians.

The HOPD model originated in part to prevent freestanding ASCs from siphoning elective cases from hospitals. To this day, ASC reimbursements are roughly half of what HOPDs get from Medicare and commercial payors for the same procedures. So why are hospitals willing to cut their reimbursements in half to embrace the ASC model?

“If you look at the revenue numbers, it does not make financial sense for hospitals to develop ASCs,” says Joan Dentler, MBA, founder of Avanza Healthcare Strategies, a healthcare advisory organization in Westchester, Ill. The 25-year veteran of the ASC space says that as surgery centers have proven themselves safe and efficient sites of care, CMS and payors have increasingly demanded more for their money out of hospitals.

“As ASCs started proliferating and their outcomes were as good if not better than in the hospital for the same cases, payors and CMS started ratcheting down what the hospitals get paid. Why should they pay more?” asks Ms. Dentler. Health systems now accept that same-day, non-urgent surgeries are inexorably moving out of hospitals due to factors including patients with high-deductible plans and payors demanding greater value and convenience, as well as the importance of lowering infection risk by not mixing healthy patients presenting for elective surgeries with critically sick patients who require inpatient hospital care.

“Hospitals realize these are elective cases, and if they’re expensive, a lot of patients won’t have them done,” says Ms. Dentler. “They’ll live with a knee that hurts as opposed to receiving a total knee replacement; they’ll live with not being able to see very well rather than have their cataracts taken care of. ASCs are also much more efficient than going to a hospital for the patient. The patient preference for ASCs is giving the hospitals a lot of headache and heartburn.”

Patty Shoults, MBA, BSN, RN, CNOR, CASC, is executive director of ambulatory surgical services at AdventHealth, a nonprofit healthcare system headquartered in Altamonte Springs, Fla., that operates facilities in nine states, including numerous ASCs — almost all joint ventures with physician-owners, some with ASC management companies involved. AdventHealth wholly owns and operates two ASCs, but Ms. Shoults says they are set up for future co-ownership with physicians.

Ms. Shoults says the HOPD model remains viable for patients with higher risk factors, but the joint venture ASC model appeals to hospitals for several reasons. “Hospitals are really trying to focus on complex surgeries in their main surgery areas,” she says. “If you’re having outpatient surgery at a hospital, it’s very easy to be bumped or delayed because a sicker patient came in who needs emergency services.”

She says AdventHealth attempted to convert one of its HOPDs to an ASC but abandoned the idea. “We figured out pretty quickly that when you have physician ownership, you need to relicense the entity, which means it loses all of its existing payor contracts,” says Ms. Shoults. “You need to start the whole process over just like a new build.”

Ms. Shoults says health systems like hers prefer partnering with physicians on ASCs. She say physicians are permitted to have ownership in ASCs under the “safe harbors provision,” by which the ASC becomes an extension of their medical practice, and a certain percentage of their volume and income must be generated from the ASC. As such, says Ms. Shoults, they focus on efficiency and cost management at the ASC. “To protect the ASC entity, there is usually noncompete language that prevent physicians from leaving the ASC and opening or joining a different ASC down the street,” she says. “This stabilizes the ASC, in my opinion.”

While AdventHealth’s ASC joint venture efforts haven’t involved private equity (PE) investors, Ms. Shoults says these firms are buying medical practices that have ownership in ASCs or are building their own. As for ASC management companies, AdventHealth views them as beneficial partners because of their expertise. Some of its joint venture ASCs are variously co-owned or managed by these firms. “Most hospitals don’t have the business acumen to run surgery centers,” says Ms. Shoults. “They try to run them like hospitals, which could put them out of business.”

Ms. Dentler says many hospitals aren’t as warm to the idea of ASC management companies being involved in their joint venture surgery centers for numerous reasons. However, over time they often change their tune. “A lot of health systems, once they have multiple surgery centers, realize it makes more sense to develop an internal ASC division or department, and they are hiring away strong talent within the ASC management companies,” she says. “The ASC still has its independence, while the hospital has a team that’s overseeing its investment. For the health systems doing this the right way, that team are not hospital people, they’re ASC people.”

The rise of private equity

Private equity interest in health care is nothing new. Since the ’70s, PE firms have been involved in arrangements with large medical groups on the hospital side of things. But over the past five years or so, there’s been a marked increase in PE’s involvement in the ASC ownership, which makes sense. When surgeries began migrating out of hospitals, the margin potential — or the ability to achieve maximum profit — became apparent to those outside of the healthcare industry. The potential of those margins is what ultimately drew private equity to the ASC market, says Daniel K. Zismer, PhD, co-chair and CEO of Associated Physician Partners in Stillwater, Minn.

Dr. Zismer says private equity firms understand the fact that many surgery centers are at a crossroads. Many established physician-owned surgery centers are in need of recapitalization, have aging physicians who are considering buyout options or both. “PE firms are smart enough to see ASCs are thinking about buying out before recapitalizing,” he says. “They know there are surgery centers that couldn’t afford the buyout if certain high-producing surgeons decide to leave.”

PE firms, of course, can afford it, and proponents of PE’s rise in the ASC market say the industry needs access to private capital because of the factors Dr. Zismer mentioned as well as the rising costs of building and outfitting surgery centers. “You used to be able to build a surgery center for one or two million,” says Danielle E. Golino, Esq., partner with McDermott Will & Emery LLP in Miami, Fla. “With all the uninterrupted power source requirements and high-tech equipment it takes to build cardiology and total joint centers today, it could cost stakeholders $5 million-plus.”

On the most basic level, Ms. Golino says private equity is simply a method to allocate capital to markets that are in need. “It’s an important catalyst in fueling the movement of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting, which requires large amounts of capital to build larger ASCs, acquire robots and the latest equipment, and negotiate more complex shared savings models with payors,” she says.

Critics of private equity cite the business model built around buying and selling quickly (typically within a five-to-10-year window) as well as the high bankruptcy rates of facilities connected to PE investment (osmag.net/bankrupt), but Ms. Golino says the criticisms are often exaggerated and misguided. “I don’t think it’s right to say private equity funds have a forced exit at five years and then they need to sell,” she says. “They can extend the hold periods, create continuation funds or structure minority recaps. Even after the first private equity fund exits the platform, the improvements that private equity fund brought are not lost — those improvements stay with the platform.”

Whether you’re for or against the increase of private equity in the ASC market, the trend is only likely to grow moving forward — barring any major legislation or government action that discourages PE’s industry growth [See sidebar, page 19]. As Dr. Zismer puts it: “Private equity has a clear path to ASCs.”

Keeping investors at bay ... for now

Two years ago, we chronicled Excelsior Orthopaedics’ efforts to remain independent by keeping calls and emails from private equity firms at arm’s length. Those feelers still come in, but Excelsior managed to hold the line and launch a $6.2M expansion project that includes four new ORs in the group’s Buffalo (N.Y.) Surgery Center.

“We get fishing calls and mass emails from groups that don’t know anything about our market, who we are or what they could add to help us grow,” says Excelsior CEO David Uba, MBA. “I’m typically slow to respond, if I do at all.”

While such efforts might have slowed a bit nationally due to high interest rates, Mr. Uba says he has a fiduciary responsibility to investigate whether private equity would work for his company. So guest speakers will present a PE 101 course at the Excelsior’s annual retreat this year just in case such an arrangement might one day work for the group. Mr. Uba remains skeptical.

While private equity does come with resources and cash, they also borrow money once they partner with a group to make investments in technology and other parts of a growth strategy that needs to be paid back, notes Mr. Uba. Also, a recent study that appeared last month in the journal Health Affairs Scholar says more than half of PE healthcare acquisitions are sold to secondary PE firms within three years.

“That’s the fear,” says Mr. Uba. “If you don’t maintain enough control initially, the PE group could sell their share and the further you go down the chain, the less control you have over your practice.” While the upfront cash infusion is nice for physicians to bank, they also must accept that they’ll make less money moving forward because the new partial ownership partner will get a share.

“Physicians get in and stay in private practice because they want to control how they care for their patients and how they run their business,” says Mr. Uba. “The initial infusion of money is a nice carrot, but you have to know what you’re signing up for.” It can cost upward of $1M in fees to attorneys, accounting firms and others to just find out whether partnering with a PE firm is a wise idea.

By then, some practices just move forward because they’ve already sunk so much money into the discovery process. A successful partnership is very market-specific, and Excelsior’s position continues to be than an outside entity isn’t likely to be able to help them, as the region’s population is flat, its small health system is losing money and payors are struggling to support that system.

“We’ll take a deeper dive, but our position remains that the predictions of the downfall of privately-owned groups are premature at best as long as you have solid business models,” says Mr. Uba. “And while PE could provide higher-quality, lower-cost care by standardizing proven clinical pathways, we’re still fearful that a pure profit motive in healthcare isn’t necessarily good for patients.” OSM

The Health Over Wealth Act aims to increase transparency of private equity (PE) in health care. U.S. Sen. Ed Markey has released a discussion draft of the Health Over Wealth Act, which he says would put safeguards in place when PE firms have an ownership stake in healthcare facilities in an attempt to maintain high standards for patient care.

The proposed legislation is one component of Sen. Markey’s review of private equity’s impact on health care. Sen. Markey and U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, both Massachusetts Democrats, held a senate subcommittee hearing last month titled, “When Health Care Becomes Wealth Care: How Corporate Greed Puts Patient Care and Health Workers at Risk.”

Part of the meeting dealt with a financially struggling national hospital chain that was acquired by a private equity firm 14 years ago. The PE firm in question has been selling off its shares, and the still-strapped health system is now being sold to another health group. The broader issue of private equity’s impact on healthcare was also discussed.

“I’ll say it bluntly: turning private equity loose in our health care system kills people,” Sen. Warren said at the hearing. She said she is working on two bills: a comprehensive one she says would overhaul the private equity industry; and a narrower one that would mandate that investors face certain restrictions when they purchase hospitals and healthcare practices.

Sen. Markey says the Health Over Wealth bill, if enacted, would require greater transparency in healthcare entity ownership, put safeguards in place to protect workers, preserve access to health care and elevate the voices of workers and communities when it comes to regulating health care and monitoring hospital closures and service reductions.

“My agenda, including my new Health over Wealth Act, will ensure transparency, accountability, protections for patients and providers and guarantee access to care for every community in the country,” says Sen. Markey in a statement.

—Adam Taylor

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)