RaDonda Vaught stood in silence next to her attorney, seemingly resigned to her fate as the jury rendered its verdict. Guilty of gross neglect of an impaired adult. Guilty of criminally negligent homicide. The charges stemmed from a fatal medication error Ms. Vaught committed while working as a nurse at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) in Nashville on Dec. 26, 2017. The patient, 75-year-old Charlene Murphey, was being treated for a brain injury when Ms. Vaught accidentally administered the powerful neuromuscular blocker vecuronium instead of the sedative Versed (midazolam), which Ms. Murphey was prescribed to calm her nerves before entering an MRI machine. She died a day later. VUMC fired Ms. Vaught on Jan. 3, 2018, reportedly for not following the “five rights” of medication administration.

- Home

- The Magazine

- Article

Fatal Mistake

By: Outpatient Surgery Editors

Published: 5/4/2022

The criminalization of a medication error shook the healthcare community and has left many providers fearing for the future of their careers and the well-being of their patients.

During a hearing in front of the Tennessee Department of Health in July 2021, she said upgrades to VUMC’s electronic medical record led to delays in medication orders reaching the hospital’s automated drug dispensing units. She claims VUMC’s staff was told to use override modes in the units in order to access medications in a timely manner. “Overriding was something we did as part of our everyday practice,” said Ms. Vaught. “You couldn’t get a bag of fluid for a patient without using an override function.” A spokesman for VUMC did not respond to a request for comment.

Still, Ms. Vaught takes full responsibility for her actions. In court documents, she admitted it struck her as odd that she had to reconstitute the powdered vecuronium with saline solution when Versed comes in liquid form. She looked at the back of the vial she pulled for directions on how to reconstitute the drug it contained, but admitted to never checking the name of the medication on the front of the container. Ms. Vaught admitted to being distracted by talking to a coworker while dispensing the medication and said she should have paid closer attention to the task at hand.

The Tennessee District Attorney’s Office took the unusual step of pursuing criminal charges. During Ms. Vaught’s trial, the prosecution convinced the jury that she was negligent in administering the wrong medication. “This case is not about the nursing profession or the healthcare community,” says Steve Haslip, spokesman for the DA’s office. “This case is about the single individual who made egregious actions and inactions that killed an elderly woman. The jury, which included a long-time nurse and another healthcare professional, found Ms. Vaught’s actions so far below the protocols and standard level of care that they returned a guilty verdict in less than four hours.”

Ms. Vaughn’s sentence, scheduled to be imposed on May 13, could include jail time. Peter Strianse, her attorney, said the on-the-job mistake shouldn’t be criminalized and claimed ongoing issues involving the automated medication dispensing units at VUMC contributed to the error. In published reports, Mr. Strianse said his client was scapegoated to protect the reputation of VUMC. He did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

During the Tennessee Department of Health hearing, after which Ms. Vaught lost her nursing license, a member of the panel asked a simple and profound question: Why didn’t you read the label before administering the medication? Ms. Vaught paused before answering. “There’s no good answer,” she said. “There’s a list of things I could come up with — being distracted, thinking about other tasks, having a conversation while pulling medications — that in hindsight were not appropriate.”

Months later and minutes before entering a Nashville courtroom to learn her fate, Ms. Vaught told a Tennessean reporter that she had “zero regrets” about telling the truth. “We have not forgotten about Ms. Murphey and her family,” she said. “Not at all. Not at all. This is about creating a safer environment so that things like this don’t happen again.”

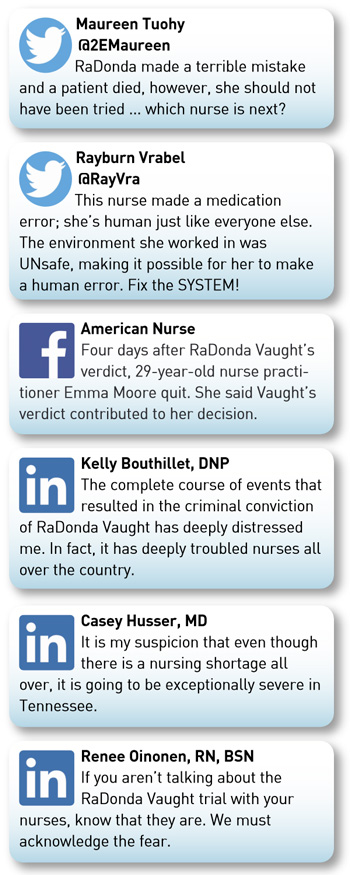

Is Ms. Vaught the victim of a broken system? Is she a careless provider whose actions led to a patient’s death? Should human errors be prosecuted in criminal courts or handled by licensing boards and civil lawsuits? Many healthcare workers who are discussing these issues on social media and in breakrooms across the country are asking themselves a more urgent question: Could this happen to me?

Healthcare professionals are concerned the verdict could contribute to the growing shortage of overworked providers who are still trying to recover from the mental and physical burdens of the pandemic. Some frontline workers are wondering why they should continue to put their own well-being on the line when a mistake could land them in jail. Others are wondering if healthcare workers will hesitate to reveal their mistakes or near-misses out of fear of being criminally prosecuted.

“It’s not surprising that the reason for these discussions is that the dichotomy between policy and law always comes down to trying to identify a winner and a loser, a right and a wrong,” says orthopedic surgeon David Ring, MD, PHD, an associate dean for comprehensive care and professor of surgery and psychiatry at Dell Medical School in Austin, Texas. “That clash is something that raises emotions and worries healthcare providers in many contexts.”

Dr. Ring knows what it’s like to be at the center of a highly publicized medical mistake. While working at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Dr. Ring performed a carpal tunnel release on a 65-year-old woman who was scheduled to have her trigger finger repaired. He was devastated, but decided to share the details of the wrong-procedure surgery, and the many factors that led to it, in a written account published in the New England Journal of Medicine. He’s spoken at conferences about the event and is continuingly willing to speak openly and honestly about his mistake. He told his story so other healthcare providers and patients don’t have to experience the anguish he and his patient endured.

“There is, appropriately, a great deal of reservation and nervousness around the idea that a medical error can lead to a criminal conviction,” says Dr. Ring. “I hope part of the discussion about this case touches on why this should be a vast exception because we understand the underlying causes of human error. We understand the role of system fixes, that practitioners drift away from best practices and we know coaching works. We understand that recklessness deserves punishment, but recklessness — true recklessness — is exceedingly rare.”

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group that provides programs, tools and guidelines designed to prevent medication errors, says mistakes made by healthcare workers should not be criminalized. ISMP President Emeritus Michael Cohen, RPh, MS, FASHP, believes the verdict could make healthcare workers less likely to be transparent and report future medication errors. “When RaDonda Vaught was convicted, the entire healthcare community lost as well,” he says. “Her conviction, which made a scapegoat of one individual instead of focusing on fixing larger, preventable systemic issues, will have serious consequences for patient safety.”

The reporting of medication errors allows healthcare workers to learn from the mistakes of others, points out Mr. Cohen, who notes that the Vaught case could also make the nation’s healthcare worker shortage worse. “If nurses believe that society, their community and the judicial system holds them to a standard of perfection, why would they want to work in health care?” he asks.

Mr. Cohen says Ms. Vaught’s honesty in reporting the incident was used against her and made her a second victim in the case. Overall, Mr. Cohen believes the trial ignored issues such as confirmation bias, inattentional blindness, alert fatigue and normalization of overrides to automated drug dispensing units.

Instead, says Mr. Cohen, Ms. Vaught was wrongly portrayed as someone who didn’t care about the patient. “The pain she was experiencing after making a fatal mistake was never acknowledged,” says Mr. Cohen. He believes flawed systems of medication practices should be fixed instead of prosecuting the healthcare providers who work with them.

Other organizations have expressed concern about the repercussions of the case. “We are deeply distressed by this verdict and the harmful ramifications of criminalizing the honest reporting of mistakes,” says the American Nurses Association in a statement. “Healthcare delivery is highly complex. It is inevitable that mistakes will happen, and systems will fail. It is completely unrealistic to think otherwise. The criminalization of medical errors is unnerving, and this verdict sets into motion a dangerous precedent.”

The Association of peri-Operative Registered Nurses (AORN) says in a position statement that the criminalization of errors might result in healthcare professionals refraining from timely and open disclosure of key error-related information, which would have a detrimental effect on the ability to freely disclose, examine and address errors. “AORN opposes attempts to criminalize unintended errors and joins many nursing and other professional healthcare associations in resisting such actions,” says the statement.

Robyn Begley, DNP, RN, chief nursing officer of the American Hospital Association and CEO of the American Organization for Nursing Leadership, predicts the verdict will have a chilling effect on the culture of safety in health care, citing the conclusion of the Institute of Medicine’s landmark report To Err Is Human that punishment of healthcare providers will not lead to safer medical practices.

“We must instead encourage nurses and physicians to report errors so we can identify strategies to make sure they don’t happen again,” says Dr. Begley. “Criminal prosecutions for unintentional acts are the wrong approach. They discourage health caregivers from coming forward with their mistakes and will complicate efforts to retain and recruit more people into nursing and other healthcare professions that are already understaffed and strained by years of caring for patients during the pandemic.”

Tanya Radic, RN, worked in the CCU, ICU and PACU during her 18-year career at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. When she first heard about the RaDonda Vaught case back in 2018, she drove more than 70 miles to her house. “She was very welcoming,” says Ms. Radic. “We had a cup of coffee together and I told her that she was not a murderer. We are nurses, and we make mistakes. I also told her that I do not know why she was chosen to go through this, but because of her, so many nurses around the world have been united.”

Ms. Radic is one of the admins behind Supporters of RaDonda Vaught, RN, a private Facebook group she created in January that now has more than 2,100 followers. She believes social media has been a terrific way for nurses around the country to connect and discuss the case. “The platform is a safe space for us to speak honestly with each other,” says Ms. Radic.

Erica Markson, RN, is a nurse advocate whose Instagram account (@the.nurse.erica) has almost 33,000 followers. She has close to 380,000 followers on TikTok, where she created an account early in the pandemic. Ms. Markson is one of the cofounders of The Last Pizza Party, a grassroots movement to support the nursing profession. Nurses from across the country sponsored her to attend Ms. Vaught’s trial in Nashville and she was able to spend time getting to know her while there. “RaDonda is very strong and focused on what’s next,” says Ms. Markson. “The past four-plus years have been a nightmare for her.”

Ms. Markson is one of the admins of the Nurses March for RaDonda Vaught Facebook group, whose members plan to gather on May 13 in the park across the street from the Nashville courthouse where Ms. Vaught’s sentencing will take place. “The purpose is simply a peaceful gathering of nurses from around the country, coming together to support RaDonda and show we are adamantly against the criminal prosecution of nurses,” says Ms. Markson. “There are currently around 700 individuals planning to attend, and we expect more to join us.”

The trial sparked a visceral and ultimately career-altering reaction in Debbie Shilobod, RN. “I watched the expert witness, a nurse who hadn’t even practiced recently, and the prosecution just slamming [Ms. Vaught],” she says. “I put myself in her shoes and thought, ‘This could happen to any one of us.’”

Ms. Shilobod has worked in health care for four decades and says being a nurse is her identity. She had planned to work seven more years until retiring, but the Vaught ruling changed those plans. She feels like she now has no choice but to end her career earlier than expected.

Ms. Shilobod, who was once disciplined for an honest medication error in which the patient survived, says the Vaught verdict will make it difficult to encourage the reporting of errors and near-misses in order to learn from the mistakes and prevent repeating them in the future. She believes the Vaught verdict sets a terrifying precedent for all nurses — particularly surgical nurses who are often pressured to expedite cases. “We take a lot of verbal orders during procedures,” says Ms. Shilobod, who has worked in the ambulatory surgery field for the past six years. “The circulating nurse is often ordered by a surgeon to administer a medication at the sterile field during the procedure.”

How can the healthcare system respond to a ruling that potentially opens the door for well-intentioned nurses to face negligent homicide charges when a mistake is made? The verdict, according to Ms. Shilobod, has given the legal system a license to prosecute nurses, and that will ultimately make health care less safe for patients. “Nurses will be extremely hesitant to follow the correct reporting process if any type of error is made,” she says.

Rebecca Gibson, BSN, RN, had just completed a travel nursing assignment and was getting ready to sign a new contract when the verdict was handed down. Ms. Gibson, who is pregnant and due in August, says the case not only prompted her to take an early maternity leave, but also led to her decision to leave the profession of nursing altogether. “My husband and I decided it was best to leave the bedside,” she says. “Working as a nurse right now is scary, and it was a stress I needed to remove from my life.”

This could happen to any of us. Just culture is dead.

— Debbie Shilobod, RN

Ms. Gibson is worried about what the future holds for the profession. “A ‘just culture’ is one that encourages the reporting of errors and near-misses in order to learn from mistakes and prevent repeating them in the future,” she says. “How many nurses will second guess self-reporting after this verdict? How many will shy away from participating in a just culture because they’re afraid of facing legal prosecution for a mistake?”

Ms. Shilobod puts it more bluntly. “Just culture is dead,” she says.

Ms. Vaught broke down in tears during the Tennessee Department of Health hearing in July. “I know the reason this patient is no longer

here is because of me,” she said. “There won’t ever be a day that goes by that I don’t think about what I did and how it’s affected her family.”

At the time, Ms. Vaught said fellow nurses and healthcare professionals have been very kind and offered their support — many of them telling her that they could have made the same mistake.

“This has served as a daily reminder of how important it is to consider that patient safety should always come first,” she said during the hearing. “The risks nurses take are much higher than they are in other careers, and that means we have to be more responsible.

“There are a lot of emotions I’ll carry with me for a very long time, but at the end of the day my life won’t ever be the same,” she continued. “The only thing I can ask is that hopefully what happened to me leads to changes that make our processes better.” OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)