Hopkins had a very good record with pressure injury prevention before reassessing and revamping its practices, but the new positioning protocols the team implemented has taken its efforts to new heights. Before the project, eight pressure

injuries occurred in approximately 4,600 surgeries. After implementation of the prevention bundle, two pressure injuries occurred in about 5,500 cases. The hospital’s new protocols reduced the injury rate from 0.17% to 0.03%. “I

don’t think it’s realistic to get to zero, especially because we do cases involving patients in the prone position that can last 10 to 12 hours,” says Ms. Myers. “We get the sickest of the sick here.”

That’s not to say the Hopkins team ignores pressure injury risks in the ambulatory setting. The Scott Triggers assessment and prevention bundle are also implemented at the health system’s ASC, where some patients are classified

as ASA 3 and some cases last longer than three hours. “That’s two criteria met for high risk of pressure injury,” points out Ms. Myers.

It’s evident pressure injuries are no longer predominantly an inpatient issue, especially now that more complex and lengthier surgeries are steadily migrating to outpatient ORs. When Outpatient Surgery surveyed surgical administrators

on their facilities’ patient safety protocols just before the pandemic, 90% of respondents said they used positioning devices or aids to limit pressure injury risks. That’s encouraging — and necessary.

“Risk stratification and pressure injury prevention protocols should be exactly the same in hospitals and ASCs,” says Lee Ruotsi, MD, ABWMS, CWS-P, UHM, medical director of the wound healing program at Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga

Springs, N.Y. “Our system’s director of surgical services and ASC director agree on this.”

The two directors say the length of time patients spend on the OR table is a critical factor in the development of pressure injuries, according to Dr. Ruotsi. “They use two hours as a point at which they feel the risk increases substantially,”

he explains. “That’s a bit more aggressive — or more careful — than most sources I’m familiar with.”

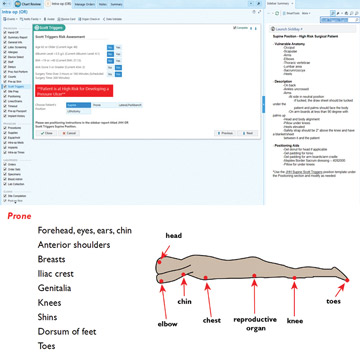

Pay particular attention to patients who are prone on the surgical table for extended lengths of time, advises Joyce M. Black, PhD, RN, FAAN, a professor at the College of Nursing at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. “The

operation might not take long,” she says, “but the front of the body, especially the face, does not have natural padding.”

Dr. Black says pressure injuries can cause damage well below the skin’s surface, pointing to instances of infected injuries on joint replacement patients resulting in implants having to be removed.

Risk stratification and pressure injury prevention protocols should be exactly the same in hospitals and ASCs.

— Lee Ruotsi, MD, ABWMS, CWS-P, UHM

“Pressure injuries do occur during outpatient surgeries,” says Janet Cuddigan, PhD, RN, CWCN, FAAN, a professor at the College of Nursing at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. “The problem is there’s

no mechanism for accurate reporting, so no one really knows the extent.”

That’s partly because pressure injuries don’t become apparent until up to 72 hours post-op, says Dr. Cuddigan. “By that time, the patient has long since left outpatient facilities and probably won’t call back to report

relatively minor Stage 1 or Stage 2 skin injures,” she adds. “I suffered a Stage 2 injury after an outpatient procedure, but didn’t let my providers know because I was much more concerned about caring for my incision.”

Dr. Cuddigan says the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI) is exploring the possibility of extending its reporting mechanisms into outpatient units. Additionally, she says, the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP)

recently voted on adding criteria for OR-acquired pressure injuries to its Root Cause Analysis (RCA) tool.

These are promising developments. Increasing awareness of pressure injury risks and developing tools to find out why they occur will lead to safer patient care. OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)