- Home

- Special Editions

- Article

The Truth of Perioperative MH Is Out There

By: Grace Patton, MBA, BSN, RN, CNOR

Published: 9/26/2024

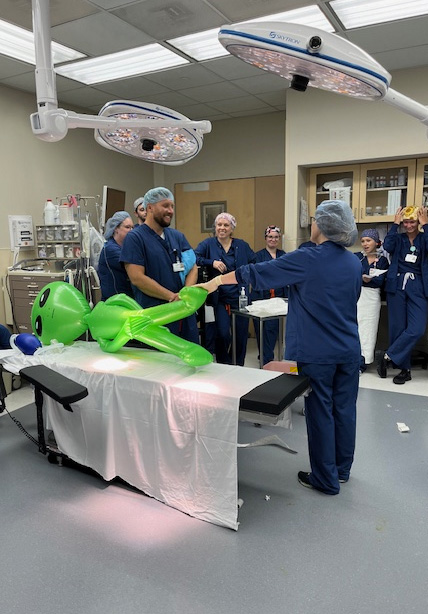

At this orthopedics ASC, clinical teams gathered to solve the mystery of an inflatable extraterrestrial who succumbed to malignant hyperthermia on the operating table.

Over the years, Outpatient Surgery Magazine has written frequently about drills to prepare perioperative and support staff for extremely rare but potentially deadly malignant hyperthermia (MH) events involving patients in our care. I don’t believe they’ve ever written about the type of MH drill we performed earlier this year, however.

Here at OAM Surgery Center at MidTowne, our orthopedics ASC in Grand Rapids, Mich., we recently held an Education Day. As part of our program, we introduced a new approach for MH emergency response preparation: a murder mystery-style drill conducted with two separate groups of prep/PACU and OR staff.

And yes, as you can see from the photos that accompany this article, the “patient” in our drill was a blow-up extraterrestrial. We just wanted to add a bit of humor to the equation, as the underlying topic of the drill was quite grim.

The mystery unfolds

The event was titled “The Mysterious Case of Patient E.”

We set up a simulated OR environment with drapes and supplies scattered throughout and our inflatable green alien “patient” on the table. The room was dimly lit, with only the overhead lights on. Eerie music was playing to enhance the atmosphere as our team members entered the room. Awaiting their arrival were three members of our ASC’s leadership team in everyday life: Prep/PACU Manager Julie Rossman, RN, BSN, CAIP; Charge Nurse Anne Manly, RN; and me, the OR manager. We served as the actors in the mystery, playing the roles of charge nurse, circulator and CRNA, respectively, and had developed pre-scripted responses for the staff’s questions.

First, however, we laid out the scenario for those assembled, who were wondering what had befallen our extraterrestrial patient:

“The staff at MAO Surgery Center [we transposed our name a bit to protect the innocent] are devastated by the death of Patient E. The OR and PACU are silent, with the team’s faces reflecting confusion and distress. After two tumultuous hours, the day is coming to an end, but the team remains baffled about what led to Patient E’s death.”

We then stated that the groups of staff would serve as quality managers on the case and performed a root cause analysis to determine what exactly had happened to the deceased Patient E.

All the OR’s a stage

The teams were then asked with whom they would like to speak first. At that point, we responded to their questions using our prepared script. Here’s how it went:

Circulator: I really don’t know what was going on. I was charting and all of a sudden the patient started deteriorating, alarms were going off and I just ran up to the head of the bed. That’s where everything got weird. Ugh, I just need a minute to think it over, can we take a break...?

CRNA: Well, this patient shouldn’t even have been here in the first place. You know why. Didn’t you read the chart? It’s obvious, if you ask me. Why don’t you go do your job first and then come talk to me?

Charge Nurse: Well, I came in when things were really going downhill. Did you talk to the others first?

[Using a prop chart, the team was able to determine from the Blue Sheet that Patient E had a first-degree relative — their mother — with a history of MH. One group found this rather quickly, while the other did so with some prompting.]

CRNA: Oh, so you did read the chart finally. Yes, I know we are not supposed to do first relatives of MH, but I was giving a break in that room and didn’t see it in the patient history. But anyway, I started to notice the warning signs of MH. If you’re so smart, you tell me what they are.

Circulator: I didn’t know that was in the policy. No one ever told me about MH!

Charge Nurse: When I onboard and review annual policies, I see the MH policy. It is terrible that no one noticed it in the chart. Usually, the phone nurse catches it and makes a note to have the surgery canceled by the office.

[The team stated the first two signs of MH crisis — they found in the anesthesia chart that Patient E’s ETCO2 had increased and their temperature had risen.]

CRNA: Yes, those are the signs I witnessed, and I charted them right away. I told the nurse that the patient was having an MH crisis.

Circulator: Yes, the CRNA let me know that the patient was having an MH crisis and to call a number, but I had no idea where that number was or why we need to call it. But I also had to help Dr. Matelic and the team count sharps, get dressing cuts and finish up what they were doing.

[The team pointed out that this was poor practice, and that the physician should close the wound and cover it with dressings. In emergency situations, the physician should prioritize anesthesia and the patient over completing the surgery.]

Charge Nurse: I was counting meds at that time and didn’t know what was going on. No one called me until later.

[The team agreed about where to find the number on a poster. They also all said they would call the charge nurse or overhead and 911 at the same time.]

Circulator: Oh yes, the CRNA said it was on the posters in the OR. When I called the number, he asked me to turn off gases, but I wasn’t really sure what gases he was talking about. So I told the CRNA to do it. I don’t know if she did or not.

CRNA: I shut off the volatile gases and told the circulator to call the charge nurse if she wasn’t going to be helpful.

Charge Nurse: I got a call finally that they needed help in OR #2. I went into the room and asked what was happening.

[The staff agreed they would tell the charge nurse to grab the MH cart when they first called them. They were then asked which volatile gas needed to be turned off. All of them correctly said sevoflurane. Anesthesia added that desflurane and succinylcholine can also trigger MH.]

Charge Nurse: I called 911 and then told the circulator to go get the MH cart. When she returned, the CRNA yelled at her to get dantrolene started.

Circulator: Yes, I went to go grab the MH cart after the charge nurse told me to get it. I brought it into the room, but didn’t really know what to do next.

CRNA: I had to tell the nurse to grab dantrolene from the cart and start administering it. She should have known how to draw it up using the calculation. Can you even do that? Show me!

[The staff used expired dantrolene to draw up and dispense the correct dose of 250mg. They worked as a team to draw up multiple doses of the medication. There was a lot of shouting and discussion about how difficult it was to draw it up. The first group stood out, as it used good communication and designated tasks to various people.]

Circulator: Are you sure that was the correct dose? I think I told them 125mg.

[The staff quickly responded that they knew that was the wrong dose!]

CRNA: I don’t remember the exact dosage. I just remember them administering it.

Charge Nurse: I didn’t doublecheck her work. I just went with what she said. I was getting transfer papers around for the ambulance. But the patient wasn’t getting any better. So we used the rest of the protocol and knew the ambulance was on the way.

[The staff stated the rest of the MH protocol, including cooling the patient with ice packs and continuing administration of dantrolene if the initial dose was unsuccessful.]

The scenario ended as the staff looked on. The patient was deteriorating, the ambulance was arriving, but Patient E had coded and was unable to be revived. Patient E was pronounced dead, and their death brought home to staff what the dire consequences could be if our MH emergency protocol wasn’t followed properly.

Action items

As the staff navigated the mystery, they learned more about the signs, symptoms and management of an MH crisis. They even had the opportunity to practice administering expired dantrolene to the “patient.”

The engaging and interactive format of the mystery not only facilitated learning in a fun environment, but it also provided an opportunity for our teams to reflect on the exercise afterward and discuss improvements we could make to our MH emergency response protocols. For example, after the drills, we decided to alternate staff monthly for checks of emergency equipment, and to set roles for each person in the room during an MH crisis.

Performing the mystery drill with two small groups instead of a large, more crowded one worked well for this project. If you’re considering doing something similar, I suggest breaking your teams up into small groups and staging the drill multiple times. Our “mystery” drill was a memorable experience for all, and we believe it was much more effective than having our staff read printed handouts or a PowerPoint presentation on a computer.

We’re all still a little sad about poor Patient E. After all, the extraterrestrial came all the way to our surgery center for a procedure but expired in our OR. We never want that to be a possibility again.

Because of this shared experience, we’re much more confident it won’t. OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)