The elderly woman left your facility with a tiny incision in her back and a gaping wound on her chin — one the expected scar of spine surgery, the other the unwelcomed scab of a pressure ulcer. Your OR team could have avoided this gruesome outcome had they followed the 5 guidelines in “The Standardized Pressure Injury Prevention Protocol” (osmag.net/upWE4W) I co-authored:

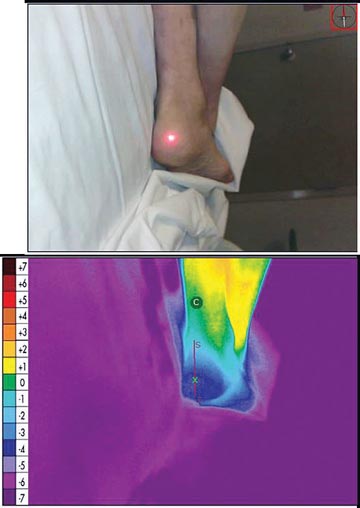

1. Pad the patient. The No. 1 way to prevent pressure injuries is to apply foam dressings or gel cushions and pads to where patients come into contact with the bed, especially to areas of risk such as the sacrum and the heels.

Next, take a look at the mattresses on your OR tables. Gel pads that are ½ to ¾ of an inch thick work well. There are also thinner pads, about 3⁄8 of an inch, that have parallel columns of air that inflate and deflate during the case to change the pressures against the patient’s skin. Inflatable waffle mattresses have little pockets of air with venting holes in between that let air flow and moisture vent to keep patients dry. Patients having surgery while in a prone, face-down position need dressings applied to their face, chest and chin. The front of the body doesn’t have a lot of padding and ulcerates very rapidly.

2. Assess your patients. The ASA score, which anesthesia providers use to assess a patient’s fitness before surgery, is the best measure of a patient’s risk of pressure injuries. The higher the ASA score, the less tolerant tissue will be to pressure. It’s easy to see someone in their 70s getting a knee replacement who looks reasonably healthy and assume she’s not likely to get a pressure ulcer when in fact she could be a high-risk candidate. It doesn’t take much time or friction to trigger some kind of pressure wound. It’s also important to know how long the patient’s surgery is going to be. Once you get to 3 hours of surgery, the risk of pressure injuries goes up 40% every 30 minutes.

3. Skip the Braden Scale. The Braden Scale doesn’t help predict the risk of surgery-related pressure injury or ulcer. The measurement was designed for hospital settings, and patients in outpatient facilities are awake, alert and ambulating after surgery. They don’t have the risk factors of a hospitalized patient who is heavily sedated and can’t move in bed. If you’d like your nurses to have a paper-and-pencil fixed risk assessment measurement, I would have them do it with the Scott Triggers Tool (osmag.net/Qou5QQ) instead.

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)