- Home

- Article

Rightsizing Regional Anesthesia

By: Julie Rossman, RN, BSN, CAIP

Published: 3/13/2024

At all-ortho OAM Surgery Center at MidTowne, nerve blocks help get patients discharged more quickly while keeping service lines humming.

Regional anesthesia has become a core component of our workflow at OAM Surgery Center at MidTowne. We perform orthopedics procedures only, averaging between 25 and 35 cases per day, from total joints to hand and wrist procedures and everything in between. I’d estimate that anywhere from half to two-thirds of our procedures involve our regional anesthesia method of choice: peripheral nerve blocks.

I’ve been here for about eight years. Our use of nerve blocks predates my arrival, and I’ve seen our usage grow substantially over that time. We’re now doing much more with regional anesthesia than ever before, and as we’ve brought more surgeons into our ASC, nerve block utilization has only risen. Our hand surgeons, for example, really rely upon regional anesthesia, but almost all subspecialties will utilize it at some point. I’d say about 75% of our total joints patients receive regional anesthesia in conjunction with a general anesthetic. Almost half of our sports procedures, including knee and shoulder surgeries, employ regional blocks. While many of our blocks are completed preoperatively, some of our doctors use them postoperatively for ACL repairs or open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) procedures.

Clinically, the appeal of using nerve blocks is to make patients more comfortable; they also help keep our patients safer postoperatively. Our patients don’t require as many narcotics because they’re comfortable from that nerve block doing its job. Preoperative nerve blocks also help patients wake up after surgery a little more quickly — not as nauseous or as “fuzzy,” because fewer narcotics are needed.

At discharge, we give patients instructions advising them that the block that is preventing them from feeling post-op pain will wear off within 24 to 48 hours, and they should start taking their prescribed pain medications before it does so. This provides them a nice, smooth transition at home. If they follow their instructions, they don’t wake up in pain when the block wears off, for example, in the middle of the night.

Block nurse alternative

We like to say we’re a small but very mighty ASC. We have five pre-op bays and four ORs. Three nurses staff the pre-op area. Patient care is one-on-one — one admission at a time. Two anesthesiologists use our pre-op area as home base. One is consenting patients, while the other’s primary purpose is to perform blocks and provide CRNA/AA breaks. We don’t employ a dedicated block nurse as some facilities do. Instead, a float nurse or occasionally our charge nurse helps with pre-op blocks when we’re busy.

In the morning when everybody’s running around excited to start the day, anesthesia likes to wait until it’s absolutely necessary to apply the block for the first case. That way, they have time to see the rest of our early-morning patients, everyone can iron out any kinks before the day starts without rushing, and we have a calm start to our day. Typically, we place each patient’s block about a half-hour before surgery to extend its effectiveness.

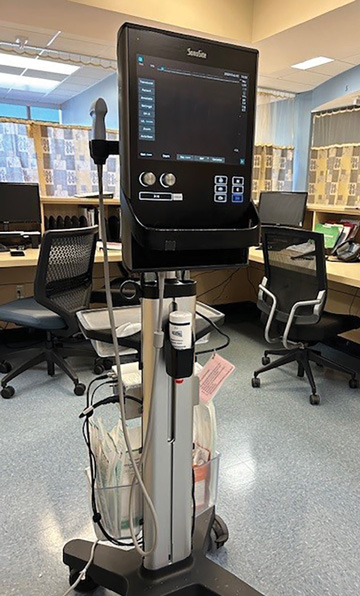

Our anesthesiologists use one of our two ultrasound machines to place blocks. One resides in our prep area and one is in our PACU area in case of rescue block situations for patients who experience unusual levels of post-op pain. Ultrasound helps the anesthesiologist increase both safety and efficacy when placing the block. They can see and target the nerve clearly on the screen so they can place the block more precisely. Most of our providers prefer ropivacaine or bupivacaine for the block, occasionally adding dexamethasone or epinephrine.

Some of our anesthesiologists use a nerve stimulator to help place blocks. This device, which pulses an adjustable electrical current to the tip of the needle that stimulates the nerve, makes the patient twitch a bit when the needle gets close to the nerve. It’s often used for patients with difficult anatomy, because it can be more challenging for the provider to see where the block should be placed on the ultrasound due to the depth of the patient’s tissue.

Safety first

We monitor for patient safety the entire time we place blocks. The nurse hooks the patient to a machine that monitors their heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen level. We place oxygen on all patients receiving a block. The nurse takes a set of vitals pre-procedure and immediately post-procedure, and we check vitals every 10 minutes until the patient is brought to the OR. Our nurse also visually monitors the patient during block placement. An accidental motor response, for example, might indicate the needle is touching or even inside the nerve; the nurse will immediately alert the anesthesiologist, who stops advancing the needle. The patient’s privacy curtain is open so nursing can keep eyes on them. Their family is also often in the room, and there’s a call light they can press.

We haven’t had a patient safety issue with blocks due to our attentiveness, collaboration and strong protocols. One key component of our safety process is a block time out performed by the anesthesiologist, nurse and patient. They check the name band, date of birth and the side and extremity where the procedure will be performed. The anesthesiologist makes a little mark on the area of the nerve block in pre-op just like the surgeon would for the location of an incision. All of this is done before any medication or sedation is administered.

The time out is important to mitigate risk. When everybody’s talking and the pre-op area is busy, the potential exists for an anesthesiologist to block the wrong arm or foot. While patients are usually aware of what’s happening, they also can get distracted by excess chatter. Performed diligently, the block time out eliminates those risks.

For some procedures, we employ monitored anesthesia care (MAC) with a block. In cases where a general anesthetic might be indicated but there are concerns about the patient’s health status if it’s applied, anesthesia may convert the case to MAC with a block. The patient doesn’t need to be intubated, feels comfortable, wakes up more quickly with less anesthetic, and breathes on their own.

This scenario illustrates that patient selection is crucial. While potential problems are rare, danger exists for certain patients. For example, if a patient undergoing shoulder surgery has lung pathology, they are at high risk for complication because the block could numb the phrenic nerve that goes to the lung. In that case, anesthesia staff would deem regional anesthesia a higher risk or even inappropriate.

In PACU, we sometimes apply what we call a rescue block to further relieve post-op pain if the patient needs it. This most frequently occurs after extremity surgeries such as tendon repairs and certain ORIF procedures. Rescue blocks are also popular with a couple of our surgeons who prefer not to use pre-op nerve blocks. They wait until after the surgery and if the patient needs a rescue block, it’s available in PACU.

Efficient for patients and providers

Our reliance on pre-op blocks makes us a little busier on the front end but brings higher patent satisfaction on the back end. When we use regional anesthesia, patients wake up more quickly and are ready for discharge sooner, which keeps our schedule humming.

Patients seem to like it, especially when they understand exactly what the injections will accomplish. In pre-op, the anesthesiologist talks to them in depth about what they’re going to feel.

Postoperatively, they might need a gentle reminder. In PACU, for instance, a patient might ask, “Why is my hand all tingly?” They forgot they received a block, so we remind them about it. Repeat patients will often remember the block they had before: “Oh, I had this done last time. Are you going to do it again?”

There’s no doubt regional anesthesia is a patient satisfier, but it’s just as satisfying on the facility side. It makes our days move more smoothly and predictably, and it allows us to safely treat more patients every day using the space we have. OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)