- Home

- Article

Prioritize PONV Prevention and the Challenges of Rescue

By: Jawad N. Saleh, BS, PharmD, MCSO-c, BCPS, BCCCP

Published: 3/12/2024

It’s a bigger issue than many providers realize, and poor planning can wreak havoc on length of stay, reimbursements and patient satisfaction.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is the most underrated postoperative complication. It rarely gets the attention it deserves, and it’s our patients who suffer most as a result.

Rethinking PONV

Part of problem lies in our understanding of the condition. We haven’t been able to fully debunk the common myths surrounding PONV, and many providers still believe high-risk status is much lower than it is actually is. That’s a costly mistake when you consider PONV can impact surgery outcomes, extend average length of stay time and cripple facilities’ patient experience scores. Plus, with CMS steadily shifting its focus to a new paradigm of “Value-Based Care” and increasingly setting its sights on healthcare quality over quantity, there are significant financial implications as well. Specifically, under the agency’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS Measure #430: Prevention of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting Combination Therapy), CMS monitors the compliance of measures taken to prevent PONV, and noncompliance will result in Medicare payment adjustments.

A holistic approach to PONV prevention — one that combines optimal medications with research-backed alternative therapies — centered around identifying at-risk patients and keeping them at ease and hydrated before their surgery can work wonders in keeping your nausea and vomiting incidents low. Here’s how to make that happen.

• Bring in the best. To combat PONV effectively, everyone on the perioperative team must be on the same page. That only happens when there’s a detailed, easy-to-follow and evidence-based policy in place for staff to use as a resource. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel here. Organizations such as the Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia, the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses each offer clear guidelines facilities can use to model their policies after. The Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting is another invaluable resource. Make sure your policy details PONV risk factors and includes step-by-step instructions for both prophylaxis and treatment/rescue options.

• Leverage technology. Use your electronic health record tools to create order-sets, Best Practice Alerts and Clinical Decision Support systems to guide your team on managing PONV. For instance, one of our organization’s basic alerts will read, “This patient has >2 risk factors for PONV – requiring >2 agents for prophylaxis,” and a clinical decision support tool will state, “If no relief with metoclopramide, then give Zofran.”

• Educate strategically. Yes, your staff needs to be trained on all the recommended agents for prophylaxis, but more importantly, they need education on rescue agents. Reason: We have limited treatment for rescue, and the process can be extremely challenging. Every agent has its drawbacks, so success is contingent upon your team being knowledgeable in this area. For instance, with ondansetron, staff needs to be aware of “QT prolongation and caution with underlying heart conditions.” For Promethazine, there’s a black box warning for tissue necrosis; extravasation.

• Perform continuous assessments. To continue improving your PONV prevention efforts, do continuous assessments on both the quantitative side — KPI measurements, benchmarks and compliance monitoring — and on the qualitative side — patient experience scores from OAS CAHPS surveys (See Cover Story), PROMS and other smaller surveys, interviews and reviews.

Putting prevention techniques into practice

With a solid policy and protocols in place, prevention comes down to consistently applying these techniques to keep PONV at bay.

• Technique 1. Make sure the basic prevention tactics are in place. Multimodal, opioid-sparing anesthesia that avoids the use of volatile anesthetics and nitrous oxide exposure are proven and effective PONV risk reduction interventions.

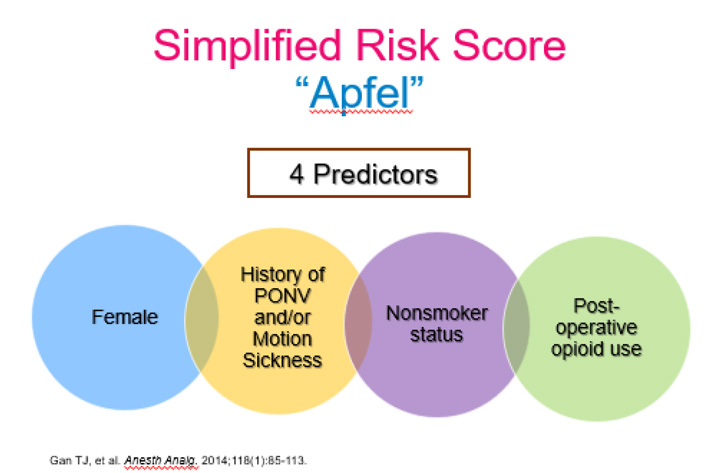

• Technique 2. Follow a consistent method for capturing PONV risk factors for every patient who enters your facility. This step is critical; properly managing PONV prophylaxis ultimately comes down to the number of risk factors a patient has. My advice: Keep it simple. While there are numerous risk factors to watch for, the Apfel Simplified Risk Score (See graphic below) is an extremely effective tool that relies on just four PONV predictors: female, non-smoker, previous history of PONV and post-op opioid use. I can’t stress enough how important this step is, as the risk factors a patient presents with will determine how many agents are needed for prophylaxis.

When developing or revisiting your PONV policy, keep these four areas front and center:

- The risk factors. This helps distinguish how many agents are needed for prophylaxis.

- The intention. Is the intervention for prophylaxis or treatment?

- The patient (past medical history, age and medication list). To assess optimal agents, look for any drug-disease and drug-drug interactions.

- The timing. For prophylaxis, know which agents to give before surgery, before induction, time of induction or end of surgery.

Reminder: A different class of medications must be given for treatment if rescue is needed within six hours of prophylaxis medications.

—Jawad N. Saleh, BS, PharmD, MCSO-c, BCPS, BCCCP

• Technique 3. After determining how many agents are needed, the next step is determining the optimal medications. For each risk factor a patient has, an additional medication will be needed. Most providers generally use dexamethasone and ondansetron as a baseline regimen for PONV prophylaxis because it’s both effective and cost-effective, but complacency can happen if providers don’t properly account for all predictors. Add medications with each risk factor accordingly.

• Technique 4. The most challenging part of the process lies in choosing optimal rescue medications for the treatment of PONV. Rescue agents can differ from most prophylaxis agents, and they require a faster onset. Therefore, it’s critical for your OR team to know any potential adverse effects of these medications. Fun fact: An agent that’s given during prophylaxis that’s also eligible to be given as a rescue medication cannot be given if the prophylaxis dose was administered within a four-hour period. This limits providers’ options significantly. For instance, you can’t use ondansetron immediately after surgery. Bottom line: Make sure the approach and preferred regimens are clearly stated and simplified for all clinicians.

Consider emerging research

In addition to the traditional prophylaxis and rescue measures just described, the emerging research has shown several non-pharmacological options are effective in preventing PONV. Acupuncture (stimulating the area between the two tendons on the patient’s wrist, which is known as the P6 acupuncture point) and aromatherapy (an inexpensive, easy-to-implement measure that frequently uses ginger, lavender or peppermint scents) are the most common. In fact, facilities frequently use these methods to complement their standard traditional protocols. Fluid therapy (preoperative fluid resuscitation), acupressure and chewing gum have also shown some benefits.

On the pharmacological side, newer dopamine antagonists such as amisulpride and a new IV push formulation of NK1 antagonist aprepitant are gaining some traction. But the most exciting new research I’ve seen focuses on pharmacogenomics in PONV. Published studies show a better understanding of a patient’s genetic background can help decrease incidence of PONV.

Specifically, ultra-rapid metabolizers of CYP450-2D6 may be associated with reduced antiemetic efficacy of ondansetron, and the D2 receptor gene polymorphism has been linked to an increased risk of PONV. Another example: With a better understanding of the gene polymorphism in the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (CHRM3) rs2165870, in combination with the Apfel Simplified Risk Score, we can independently predict PONV sensitivity.

Seeing is believing

PONV is much more common and problematic than many providers think, and we need to change how we approach this costly, satisfaction-killing problem. We know that every risk factor increases the chances of PONV by 20%, but it can be powerful to show just how many patients are truly at risk. I once did a PONV lecture at a conference where 160 women and 100 men were in the audience. I asked the women to raise their hands and told them they already had one risk factor simply due to their gender. I then asked them to lower their hands if they smoked. Only 20 of the hands dropped, and 140 remained. That’s two risk factors. Now if any of the people with their hands raised had surgery, I told them their chances of receiving an opioid would be high, which adds another risk factor and puts all 140 (60%) of the individuals with their hands up in the high-risk category. Finally, I asked those with their hands raised if they got nauseous on airplanes or in the back of vehicles often. Fifty of the 140 still had their hands raised at this point. When I told those 50 women they had four risk factors and an 80% chance of suffering PONV, it was an eye-opening moment for everyone in attendance. Much more powerful than simply showing a slide outlining the risk-factor/percentage increase.

Whoever first said an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure could very have been talking about PONV. Research shows that many patients are more afraid of the nausea and vomiting potential of surgery than they are of the pain. Therefore, it’s in every provider’s best interest to adhere to that timeless saying and give PONV the seriousness — and resources — it deserves. OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)