- Home

- Article

Commit to 10 Minutes for Safety

By: Adam Taylor | Managing Editor

Published: 8/19/2024

Forced-air systems dry even the narrowest lumens in your trickiest-to-clean endoscopes.

Everyone is aligned with the idea that endoscopes need to be dried before they’re stored because germs thrive in their long, dark, narrow channels. At least 10 minutes of filtered, forced-air drying time is agreed-upon threshold in guidelines from the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) and GI societies.

Filling the gaps

The issue is, there’s an implementation and adherence gap by many facilities, and the noncompliance seems to be more prevalent in outpatient settings than inpatient ones, according to Cori Ofstead, MSPH, president and CEO of Ofstead & Associates, a research and consulting firm in Bloomington, Minn., that assists providers, device manufacturers and other organizations within the healthcare industry.

Not all endoscopes undergo full sterilization, a fact that surprises some nurses and physicians.

Many scopes undergo high-level disinfection from an automated endoscope reprocessor (AER).

These devices, after pumping water, detergent and disinfectant through the scope, also use an alcohol flush to dry the channels. Unfortunately, notes Ms. Ofstead, there are studies that show alcohol can actually hinder, not help, the drying process because water will fixate to the scope channels when alcohol is present.

This is unwelcome news for infection prevention efforts, since many facilities, perhaps understandably, believe that using the gravity method of drying in a storage cabinet will suffice after the scopes were disinfected in an AER and then flushed with alcohol afterward.

Ms. Ofstead and her team performed a study to see how dry scopes were after an AER cycle and an alcohol flush.

The eye-opening results were presented at the Association for Professionals in Infection Control & Epidemiology (APIC) 2024 Conference and Expo in San Antonio, Texas, and can be viewed at osmag.net/slideshow. Specifically, Ms. Ofstead and her team reviewed a drying device that attaches to endoscopes after they’ve been through the AER to see if it could dry them in 10 minutes.

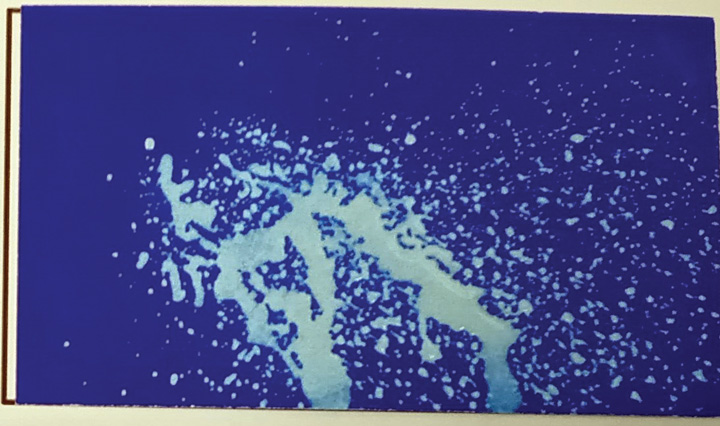

The scopes were tested after they went through AER machines and underwent an alcohol flush and air purge. The research team used small cards with blue ink on them that turn bright white if water touches the card. The results looked like dozens of little white and blue Jackson Pollock paintings. The cards were put outside distal ends, suction connecters and other parts of the scopes. “Water came out of everything — it was astonishing,” says Ms. Ofstead. “Water didn’t just come out of the instrument’s big biopsy channel. Water sprayed, splattered or oozed out of all kinds of other channels and ports.”

It was all the more troubling because the researchers hadn’t known about the extent of water that can remain in so many of the scopes’ components.

“That, for me, was the ‘aha’ moment about why we’re getting exposure to germs and microbial growth in these instruments and why we’re transmitting infections,” says Ms. Ofstead. “It’s because water doesn’t linger in just the main channel, there’s retained fluid in the whole interior of the scope.”

The drying system tested to fix the problem worked extremely well. The scope and the drying mechanism were hung from the same piece of equipment, which is something similar to an IV pole. The forced air went through all the channels and researchers found that it did indeed dry all part of the scopes’ interior in a 10-minute time frame.

“At the very end of the drying cycle, we held the same blue cards and there was no more fluid coming out,” says Ms. Ofstead. “We inspected the inside of the scopes after the drying to see if there were any puddles or droplets of fluid, and we never saw any.”

Water was originally detected in all of the 42 distal ends of the scopes studied and in one-third of the suction connecters. No water was detected in either of those areas after the 10-minute drying cycle.

This study reinforces the guidelines that say you need that 10 minutes of forced-air warming to get all the channels dry, not just the big one.

The study essentially resulted in dual findings — that the insides of endoscopes are still very wet after coming out of AERs, and that the liquid was in fact removed by the dryer. “It really reinforces what the guidelines from AORN and AAMI say, which is that you need those full 10 minutes of forced air,” says Ms. Ofstead. “And this study also showed how you need to think about getting everything dry by connecting it all — not just the big channel.”

Scopes in the news

There have been several recent outbreaks linked to inadequate drying, notes Ms. Ofstead. Some of the cases were due to human germs, but often it is waterborne pathogens that may have been in the rinse water that was used after disinfection.

It’s important to understand that many or most of the outbreaks that have been discovered involve urology scopes or bronchoscopes, some of which are commonly used in outpatient surgical settings. Obviously, all infections are bad, but infections from a colonoscope tend to be less dangerous than those from other types of scopes.

“The problem with contamination that grows on these kinds of scopes [urology scopes, bronchoscopes, etc.] is that the germs can double every 20 to 30 minutes if the scopes are wet,” explains Ms. Ofstead. “If you hang them up and put them in storage when they’re still wet, they are a hotbed of pestilence the next day.”

This poses a potential and particularly serious health risk if the scopes are going to enter patients’ lungs, kidneys or bladders. The channels of those types of scopes are narrower than colonoscopes, which makes efforts to keep them clean and dry so vital. For example, recent news accounts that stemmed from the FDA’s Adverse Event Report database discussed outbreaks from urology scopes used on multiple patients that the facility did not realize were infected. “These infections generally are from waterborne pathogens or bugs that thrive in wet conditions, and they can cause very serious illnesses among patients,” the report said. The FDA Adverse Event Report database lists a couple outbreaks with urology scopes that involve dozens of patients, because the facility didn’t realize that the scopes were infested, and used them on multiple patients. The fact that these scopes create conditions in which an array of pathogens can cause serious illness makes that extra drying time an absolutely crucial extra step.

Array of drying systems

There are multiple products to dry endoscope channels after they come out of the AER and before they get stored for the next case.

Some devices are essentially air guns or air pistols. Reviews of products by Ms. Ofstead’s group showed they take some, but not all, of the water out of the insides of scopes and are most effective for the largest internal channel.

There are also drying systems that hook up to the scope, the subject of Ms. Ofstead’s recent study. These dry the scopes before they go into storage cabinets, and connect to all the channels of the scope. One feature Ms. Ofstead particularly likes about this type of device: a staff member doesn’t need to stay with the scope during the 10-minute drying period, which could present an obstacle to using it — especially if the person tasked with the job is filling dual roles and has other pressing clinical tasks to address. She references a Stanford researcher who discovered that staff is much more likely to dry a scope with one of these devices than they are to spend the full 10 minutes using an air gun.

“We have found that corners get cut when it comes to drying in outpatient or ambulatory settings more than inpatient settings,” says Ms. Ofstead. “For a variety of reasons, they may not have the time or disposition to perform drying functions correctly. That’s why the automated drying system we tested is so appealing. You hook it up, push the button and you can walk away.”

There are also many forms of cabinets, from bad to outstanding. There are many traditional ones in which the scopes hang vertically and have poor ventilation, or none at all. “Those should be eliminated, in my opinion, because they not only don’t dry the scopes, but they also foster a wet and humid environment,” says Ms. Ofstead.

Some cabinets have forced air circulated with a HEPA filter for varying amounts of time. The cabinets that offer the most drying protection are ones that have continuous airflow and are connected to the scopes’ channels for the entire time they’re in storage.

“Those are a significant capital expenditure and take up a lot of space, so they aren’t realistic options for all facilities,” says Ms. Ofstead. “Many facilities simply don’t have the infrastructure for them.”

One of the main takeaways from the recent study is to not equate an AER cycle and alcohol-air purge with drying. Make sure the scopes are bone-dry before they go into storage.

A simple test

The little blue cards referenced in the APIC presentation are an inexpensive, quick and straightforward way to determine when your scopes are, in fact, bone-dry. Simply use an air pistol, or even a syringe, to push air through the channels while placing the cards at the other end. If the cards turn white, your scopes are wet, and you can move to conducting a risk assessment and then a quality improvement plan.

As technology evolves and the market offers better types of storage cabinets, surgical leaders need to find ways other than checking for fluid at the bottom of cabinets to assess whether scopes are dry.

We, says Ms. Ofstead, need to elevate our care of these tools to include thinking about infection control and patient risk. “A puddle at the bottom of one of your cabinets is a very high-risk situation, particularly for scopes that are used in sensitive tissue,” she says. “We need to make sure that they’re absolutely bone dry.” OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)