- Home

- Article

Anesthesia’s Role in Total Joints Success

By: Adam Taylor | Senior Editor

Published: 11/8/2022

The right combination of analgesics and anesthetics can get outpatient knee patients out of an ASC about four hours after they arrive.

Standardization is often the common denominator among successful total joints programs. Take Knoxville Orthopaedic Surgery Center (KOSC), which opened in December 2009 and has had a total joints service line for five years. It attributes its consistently good outcomes largely to its ability to handle each case the same way every time.

Retaining its staff and fellowship-trained surgeons who are dedicated to outpatient total joints (OTJ), and crafting policies and procedures that are OTJ-specific is the key to the Tennessee facility’s achievements, explains its Executive Director Beth Russell, MSN, RN, CASC. “A total joint is a total joint,” says Ms. Russell. “We set up protocols, do it the same way every time, and that’s how we got good at it — and anesthesia and post-op pain control are a huge part of why we’re successful.”

KOSC’s sister surgery center, the Advanced Orthopaedic Institute, opened in July and is staffed with surgeons who were trained on surgical robots, using them at the University of Tennessee Medical Center on patients who stayed overnight after their procedures.

They wanted robotics to be part of the new facility and the first robot-assisted joint replacement took place on Oct. 28, says Executive Director Tammy Rowland, RN, MXT, ONC, adding that it’s taken a page from KOSC’s book to strive for consistency in all its affairs.

“The basic building block of starting a total joints program is to standardize as much as possible by getting providers to agree on what should be in their order sets and their treatment of all patients perioperatively,” she says. “The win from that is huge, and it’s what’s best for patients and for your operations and throughput. When everyone’s doing things best and the same way, it makes it so much easier to train your staff.”

Ms. Rowland says the more you standardize, even down to the dressings you use and how you close the wounds, the more it helps with your materials and supply chain management, and your budgeting. “You can greatly reduce the cost variance in your cases if you can get everybody to agree on one standardized routine process,” she says.

Managing patients is paramount

Ten years ago, knee-replacement patients of all ages assumed they’d not only need to stay overnight at a hospital after their surgery, but they’d also spend multiple days at a rehabilitation center to recover. That’s the furthest thing from what today’s patients want and expect. “Nobody wants to stay in the hospital now,” says Matthew C. Nadaud, MD, the senior total joint surgeon at Knoxville Orthopaedic Clinic, which just opened its second ASC because of the practice’s massive growth. “We routinely have patients in their mid-70s with some medical comorbidities who insist on having their procedures done in an ASC. The massive shift in patients’ attitudes toward joint replacement has been incredible.” These types of patients, who are increasingly educated on the benefits of outpatient surgery, helped bring about the rapid ASC growth, which was also accelerated by a desire to avoid hospitals during COVID-19. But what advances gave patients the option in the first place? Dr. Nadaud says the answer is surprising, noting that he’s long used the same minimally invasive posterior approach whether he’s performing inpatient or outpatient knee replacements.

Our goal is to optimize the patient’s experience and recovery — and this starts before they enter the OR.

Cannon E. Turner, MD

“About 85% of my hospital patients go home the same day as well,” he says. “Patients hear lots of marketing messages about new gadgets, robots and surgical approaches, but none of that has had any effect on our ability to do outpatient surgery, which hasn’t changed substantially in years, truthfully.” The important shift, Dr. Nadaud says, has been how patients are managed perioperatively, and a key element of that is how anesthesia is employed. The anesthetic techniques have been honed to make total knees an outpatient procedure with the new patients’ motivation to be home the same day in mind, says University Anesthesiologists’ Cannon E. Turner, MD, chief anesthesiologist at Knoxville Orthopaedic Clinic.

• In pre-op. Total knee patients, with very few exceptions, get the same protocol-driven multimodal pain therapy, and it all starts in pre-op before they have an IV in their arms, says Dr. Turner.

The first component is oral acetaminophen, a pain reliever and fever reducer; celecoxib, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID); and a small dose of oxycodone. “We’re trying to minimize narcotics, which is why we’re starting off with that small oral dose in conjunction with nonopioid adjuncts in the hope that it will be the only narcotic they receive,” he adds. “In addition to patient comfort, all the oral medications are geared toward minimizing the higher dose of narcotics they would have otherwise received.”

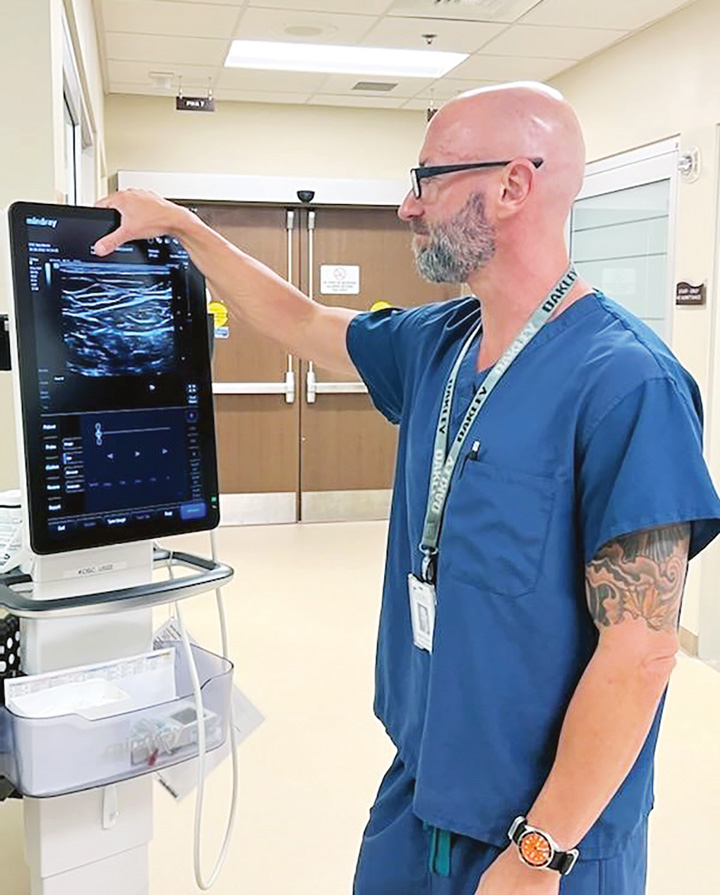

Younger patients get oral gabapentin because of its opioid-sparing effects to treat pain. It’s administered more selectively in older and other at-risk patient populations. The protocol is designed to keep the patients just sedated enough to be comfortable during and immediately after the procedure, but not so groggy that they’ll need several hours in the PACU. Male patients get an oral dose of tamsulosin to help them urinate after the surgery, one of the criteria for discharge. Next comes the spinal anesthetic, which also occurs preoperatively. Patients are given a low-dose injection of ropivacaine. “Our goal is to give the lowest effective dose, so that we have surgical anesthesia in the operating room while also promoting a timely recovery of their motor function,” says Dr. Turner. Patients get a low dose of midazolam instead of narcotics like fentanyl immediately before the spinal injection is placed, a choice that allows patients to wake up faster after their surgery. The patients sit up for the spinal injection. While still in pre-op, they’re laid down for the adductor canal and iPACK blocks, which Dr. Turner uses ultrasound guidance to place.

These are single-shot blocks with a low volume and higher concentration of anesthetic, so patients will have the appropriate analgesia with no muscle paralysis or motor block. “We keep the volume low because we don’t want patients to be unable to move their calf after the spinal wears off. That would delay their discharge because they’d be a fall risk at home,” he says.

Dr. Turner notes having two low-volume blocks helps to avert potential side effects from each of them. “Finding the minimum effective dose of everything is the key,” he says. Knoxville Orthopaedic uses 20mls of 0.5% ropivacaine for the adductor canal block and 10mls of ropivacaine for the iPACK block.

To prevent PONV, patients are also given IV ondansetron and decadron, sometimes with a scopolamine patch as well, before they go into the OR.

• In the OR. Now the patient is ready to be wheeled into the OR, where IV propofol is the sole anesthetic used via MAC sedation after the patient is draped and prepped.

Using infusion pumps to administer the drug is better than general anesthesia and intraoperative narcotics, because it allows patients to breathe spontaneously and reduces the risks of excessive sedation and nausea. “Our goal is to optimize the patient’s experience and recovery — and this starts before they enter the OR,” says Dr. Turner. “Their return to consciousness and their time in PACU is much shorter after the IV medications and propofol than it would be if we used inhaled general anesthetic gases.”

Following the procedure, one of the last things the surgeons at Knoxville Orthopaedic do is inject a combination of a local anesthetic and an analgesic into the joint. Depending on the surgeon, the local anesthetic used is ropivacaine or bupivacaine and the analgesic is ketorolac, morphine or ketamine. “The thought is that injecting right at the site, where it needs to work, will increase the analgesic effect of everything else we’ve done,” says Dr. Turner.

• In the PACU. In most cases, when patients wake up, the effects of the spinal anesthetic are regressing, the nerve blocks and joint injection are working, and they are comfortable, able to urinate, and can eat and drink.

In this phase, patients must walk up a test physical therapy staircase and, if they can ascend it, they’re nearly ready to go home — often only four hours after they arrived at the surgery center. “In terms of medication, hopefully that’s it,” says Dr. Turner. “Sometimes a patient will need a dose of something before they leave — acetaminophen, ketorolac or, in rare instances, a narcotic — but more often than not, all the work was done beforehand, so everything is optimized and they’re soon in their car going home.” OSM

When Knoxville (Tenn.) Orthopaedic Clinic started doing total joints in 2017, it was extremely selective about its patients. In fact, it started with only the healthiest ASA I patients, before eventually expanding to ASA IIs. Plus, initially surgeons and anesthesiologists met with each patient two weeks ahead of time before greenlighting a surgery. This caution was to make sure there would never be a need for a hospital transfer because a patient wasn’t ready to go home.

Today, the pre-op assessments begin with a phone call from the nurse before the patients arrive. In addition to optimizing patient’s anesthesia to hasten safe and healthy same-day discharges, each ingredient is added to the multimodal recipe at the right time to integrate into the surgery center’s overall workflow. The center flips rooms, with a surgeon operating in two different rooms on one patient at a time. After the surgeon finishes the actual joint replacement, a physician’s assistant performs the wound closure. As that’s occurring, the anesthesia team has gotten the next patient ready to go, so the surgeon can walk into that OR and make the incision.

“It’s a clockwork movement where the timing of the block placement and administration of patient medication are done in a way to ensure the patient is prepared the moment the surgeon is ready to go,” says Cannon E. Turner, MD, of Knoxville-based University Anesthesiologists, and chief anesthesiologist at Knoxville Orthopaedic Clinic. “We’re trying to maximize the flow to get patients in and out as quickly as possible, so they’re able to go home that day.”

That’s the main reason all the injections a patient receives are done in the pre-op area, which is outfitted with monitors just like an OR. Dosages are set to make sure the spinal injection will get them through the surgery and the blocks will

minimize post-op pain for a few days — all with an eye on ensuring their ambulation soon after they have their new knee. “We’ve found a way to implement an opioid-sparing regimen that limits post-op pain, avoids complications

and results in positive clinical outcomes,” says Dr. Turner.

— Adam Taylor

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)