• Antibacterial dressings. More attention is being paid to dressing the wound, which is another positive development. Antibacterial dressings include sponges impregnated with silver (an antimicrobial) and are applied to patients in

the sterile field, which is where surgeons can place the cleanest dressings on the wound. The absorbent silver-laden sponge can soak up and handle any fluids that leak from the wound.

These dressings are appropriate for all types of surgeries. They’re more expensive than dressings that are not impregnated with silver, but definitely worth it. Infections are disabling for patients, who would need an antibiotic regimen

at a minimum. They’re also potentially very expensive to treat and to litigate. These dressings can always be taken off, but work best when they’re on during the first few days of recovery.

When patients or an aftercare team take off the initial dressing in 48 hours, check the wound, then cover it again, they’re exposing the wound before it’s totally sealed. I prefer to put the antibacterial dressing on immediately after

the procedure and have it remain in place for seven to 10 days before the patient is instructed to change it. This is an effective practice because the wound is being protected during the critical healing time when it’s not yet watertight

and therefore still susceptible to contamination.

Antimicrobial dressings are completely waterproof, so it’s fine for patients to shower with them on after they go home. I tell them to resist the temptation of opening them to peek at how the wound is healing. I impress upon them that, again,

this is the cleanest dressing we can put on your wound, so it’s important to leave it on for a week to 10 days unless they really feel like something is wrong.

Some discoloration of the sponge is normal and not a cause for concern. If the drainage isn’t stopping within two or three days, if patients feel significant pain or there is some visible redness that seems to be spreading beyond the incision,

they should call their doctor. In rare cases, some people might get some minor skin irritation, likely an allergic reaction to the adhesive, so the dressing could need to be removed in those cases.

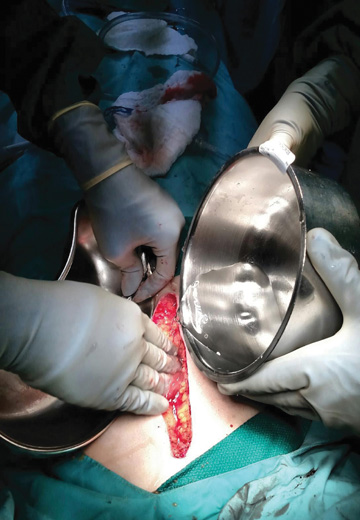

• Subcuticular closure. Staples were the standard in closing skin incisions for a long time, but there has been a significant shift in the last few years toward newer options that do a better job of closing the wound. Subcuticular

closures with some sort of thin skin adhesive such as glue create a watertight wound that I and most of my colleagues use. They’re very convenient: patients can generally shower right away with them in place, and there’s no need

for a return visit to have staples removed.

These noninvasive adhesive wound-closure products can be economical because surgeons shave precious minutes at the end of a case when closing the wound, and those minutes add up to a more efficient and less expensive day in the OR.

Every staple represents potential entry points for bacteria, so SSI risks also go down with adhesives. Patient satisfaction is an additional benefit, as significant scar tissue can be a negative even for patients who go into surgery saying they

don’t care about scarring.

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)