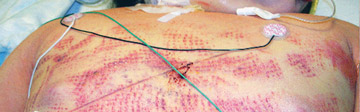

If you think residents of nursing homes are the only people who wind up with agonizing pressure injuries because they've been laying in the same position for weeks at a time, consider the case I saw while overseeing a multi-year project to develop and initiate a comprehensive pressure injury prevention program for a large hospital system.

A 19-year-old woman came to the outpatient surgery center for a mandibular surgery, which was a success. During the post-op appointment with the surgeon, however, she arrived with a deep-tissue pressure injury on her left buttocks from being in the same position on the operating table for approximately eight hours. This patient, whose mandible was healing perfectly, actually took the post-op pain medication prescribed to her not for her jaw pain, but for the pain in her buttocks. If this healthy young woman with perfect skin integrity can suffer an injury like this, you better believe older patients with comorbidities are at risk as well.

Research has demonstrated that a pressure injury can develop within minutes due to the cascade of events associated with cell deformation. In clinical practice, we have found that surgical patients immobilized for more than three hours are at risk for the development of a pressure injury. Take note, because the last thing you want is for one of your patients to visit their surgeon with a Stage 4 pressure injury on their heel, tailbone or occiput that happened when they entered the operating room for an elective procedure. Here are several ways to make sure these injuries don't happen at your facility.

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)