Think about your car. If you’re good to it, it’ll be good to you. If you change the oil every 3,000 miles, you could get more than 100,000 miles from the car. But it you abuse your car, you’re likely to have problems. It’s

the same with your instruments. Modern-day surgical instrumentation is becoming even more complicated, especially in robotics. And it’s way more expensive to fix than it used to be.

“That’s why it’s imperative to make sure your equipment is working appropriately,” says Mr. Voigt.

3 Transport with care. You can damage instruments while transporting them. Make sure that your sterile processing department is packaging your instruments in a way that follows the

manufacturer’s IFU. But that’s not all. Make sure that instruments aren’t being jostled during handling, particularly in the transport cannister.

“We see even more damage to instruments from the OR on the way to our decontamination area,” says Mr. Voigt. “I don’t think anybody is trying to intentionally damage instruments, but they’re being pushed to go faster

and faster to turn the room over. Sometimes it’s just kicking the can down the road.”

Sometimes a handful of instruments are just pushed into a rigid container after a procedure and the tips of scissors, tissue forceps or needle holders — all delicate instruments — can fall into small holes in the rigid containers and

get bent, damaged or broken.

“It’s the end of the case, they’re hurrying and they’re putting instruments into a rigid container,” says Mr. Voigt. “Damage can occur when you place heavier instruments on top of delicate instruments.”

To prevent that at CentraCare Health, Mr. Voigt has conversations with the OR team on a regular basis. If he sees something like that happening, he records it and reports it back through a process improvement method.

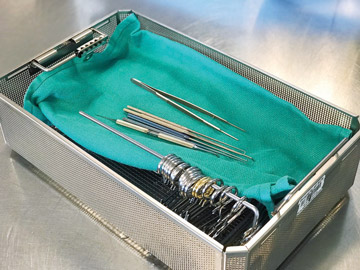

4 Segregate. Segregate your sharps from your delicate instruments. You can put them in separate containers or use a surgical towel to separate the sharps from the delicates (with

the delicates on top), says Mr. Voigt.

5 Use vacuum sterilization. Switch from gravity to vacuum sterilization — when it’s compatible with the device’s IFU — to improve the efficiency of sterilization

and cut down on the time that instruments are exposed to steam. With gravity, steam comes from the top and pushes steam through the instruments. Using vacuum pushes the steam more forcefully through the trays. It penetrates more efficiently

and gets into the nooks and crannies of the instruments and does so in less time.

For example, the dental drills used at Omaha (Neb.) Surgical Center — which have a lot of moving parts — were locking up because of being sterilized over and over. They often needed to be repaired or replaced.

“Our dental drills needed to be sterilized for 15 minutes in gravity. By switching to vacuum, we were able to cut that down to 4 minutes,” says Melissa Sawyer, CST, assistant OR manager at Omaha Surgical Center. “Now, they’re

just not exposed to the high temperatures as long. That seems to have made the repairs less frequent and extended the life of the instruments.”

6 Lubricate when necessary. When appropriate, lubricate all your instruments to cut down on repairs. Omaha Surgical Center does a lot of pediatric dental restorations, in addition

to eyes, gynecology and colonoscopies. The center was having issues with the drills not spinning because the motors were repeatedly getting stuck. To solve that problem, the center made it protocol that every time a drill came back to the

instrument room, it was lubricated with an oil before sterilization — but only the dental drills. Many of the manufacturer’s IFUs for other drills recommend that they not be lubricated.

7 Pare your instrument trays. Decrease the number of instruments in your trays and limit the trays to only those instruments being used for the procedure. This reduces multiple unused

instruments from being exposed to sterilization over and over. At Omaha Surgical Center, the eye trays used to contain around 25 instruments, some of which weren’t being used but still had to be sterilized because they were brought in

for the procedure.

“We took out those instruments that were only used occasionally and put them into peel packs and placed them in ‘cataract extras,’ little slots in our cupboards in each OR,” says Ms. Sawyer. “We cut it down to 12

instruments, so there were fewer instruments to clean every time.”

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)