Ms. Sasso says adding a lip underneath the tip of the hand sanitizer dispenser to catch drips would have prevented the nurse from hitting the floor. She's also seeing fewer cords taped to the floor — National Fire Protection Association standards state that extension cords used in the OR must be medical grade and must be adhered to equipment or the wall — and says more surgeons are standing on anti-fatigue, anti-slip mats, which provide ergonomic benefit and prevent them from slipping on fluid waste. Closed fluid waste management systems and floor-wicking devices also help to keep OR floors dry.

Additionally, wireless video routing and cords encased in ceiling-hung booms have contributed to fewer tripping hazards. Ms. Sasso also points out that the trend toward restricting access to the OR because of infection control concerns is creating more room to move and fewer people in the room who are at risk of tripping or slipping.

Scott Reeves, MD, chairman of the department of anesthesia and perioperative medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Clemson, and a team of researchers received a $4 million federal grant from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research to focus on improving patient care through human-centered design in OR. Their efforts focused on reimagining traditional layouts to improve the functionality of the room and enhance quality and safe care. They analyzed big ticket items (how are surgical booms best utilized?) and small details (how high off the floor should electrical outlets be placed?).

Dr. Reeves says some technologies, including wireless video routing, remove some tripping hazards from the floor. However, he adds, "Many experts believed equipment would get smaller as technology evolved, but that hasn't happened. In fact, advances such as robotic surgery have added equipment with very large footprints to the OR."

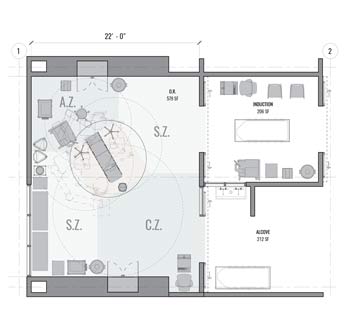

With valuable floor space at more of a premium than ever, the simplest way to keep the surgical team upright might be to reconfigure the typical OR set-up, according to Dr. Reeves. Instead of keeping the table in the center of the OR, he suggests moving it closer to the upper left portion of the room, with the head of the table angled toward the corner.

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)