Every year, physicians perform millions of off-label epidural steroid injections (ESI) to treat neck and back pain — despite the risk of rare but serious and sometimes fatal neurological side effects and despite the fact that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has never approved corticosteroids for injection into the epidural space.

Off-label drug use isn't necessarily a breach of the standard of care. The FDA considers doctors who use steroids off-label "part of the practice of medicine and not regulated by FDA." The courts, as this month's case shows, took a sterner view.

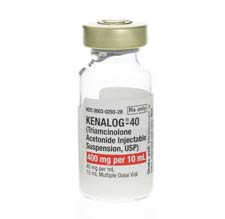

In 2013, a 60-year-old Colorado woman underwent ESI at The Surgery Center at Lone Tree (osmag.net/YoHAn4) with Kenalog (triamcinolone acetonide), which the FDA warned cannot be used for epidural injection. The patient received 4 injections of the glucocorticoid on the right side of vertebrae L1 and L2, court records show. Soon after the final Kenalog injection, in the recovery area, the patient lost motor function and complete sensation from the waist down. She and her husband sued the surgery center, and were awarded $14.9 million. She remains a paraplegic.

The side effects of Kenalog are rare and typically minimal when properly administered, but the risks are significantly greater when injected into the spine. Two years before the woman received the injection, Bristol-Myers Squibb, aware that Kenalog could cause spinal cord injury during ESI, petitioned the FDA for permission to modify Kenalog's warning label to read "Not for Epidural Use." In part, the warning now reads: "Spinal cord infarction, paraplegia, quadriplegia, cortical blindness and stroke (including brainstem) have been reported after epidural administration of corticosteroids."

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)